I

n 1970, midway through a career that lasted seven decades, P. K. Page wrote:I am a traveller. I have a destination but no maps. Others perhaps have reached that destination already, still others are on their way. But none has had to go from here before – nor will again.

Writing a person’s life must be, to some extent, like drawing a map: linking major landmarks; finding the smaller tributaries that feed into the river; getting the lie of the land, where the terrain is hard going and where it is smooth. Or maybe it’s just a useful metaphor – though one suspects that in Page’s case it’s not. As one of Canada’s early modern poets, a woman who lived almost a century and spent the better part of it making some of the most startling, masterful writing we’ve seen, P. K. Page cut her own path.

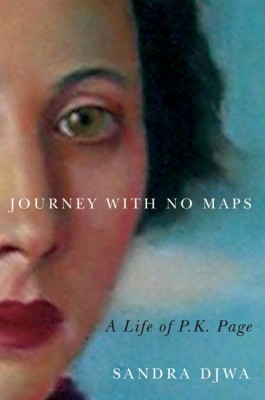

Journey with no Maps

A Life of P.K. Page

Sandra Djwa

McGill-Queen’s University Press

$39.95

cloth

424pp

978-0-7725-4061-3

Djwa first met Page in 1970, when she invited her to read for her poetry class at Simon Fraser. “She was absolutely wonderful,” Djwa recalls. “Dynamic. Very nervous. But she read beautifully, her voice was full of emotion. All the students were electrified. One poem that she read, ‘Arras,’ was difficult but we were spellbound anyway. She was also very vibrant and attractive, and wore a purple cape. She looked like a poet.”

In 1987, Djwa wrote a biography of F. R. Scott, which puts her in a unique position as Page’s biographer. The two poets, who met in Montreal and worked together on Preview magazine, had a romantic relationship that lasted many years. Scott was married to painter Marian Dale; the couple had an open marriage, though not without its share of jealousy and misunderstandings. Page’s relationship with Scott went through various stages of secrecy and anguish, and Page finally ended it in the late 1940s, though she and Scott continued to correspond and send work to each other (and, presumably, work through their feelings for each other in verse). “I tried to present both perspectives fairly,” Djwa says. “To some extent both were caught in a situation not entirely of their own making. I had worked previously on Scott’s biography and may have begun Page’s biography with some residual sympathy for him. However, as the work progressed it soon became clear that she was the more vulnerable partner and my sympathies switched. In researching Page’s biography I recognized how extraordinarily difficult her situation was for a young woman of her character and upbringing.”

The book’s account of Page’s early life gives insight into the strength of character and fierce curiosity that shaped her. An early photo shows a confident Page, dressed only in a loose pair of shorts, standing with her brother and father, the latter’s military medals on display and the former in his birthday suit. It’s an unconventional family portrait of an unconventional family. Lionel Page treated his daughter as an equal, writing her forthright letters when he was away on duty and encouraging her to pursue her creativity. Her mother, Rose Page, illustrated books of verse for her children, saw auras on people, and had accurate premonitions about the future, igniting in P. K. the idea that there were forces at work outside the material world.

Journey With No Maps is not just a biography of a poet, but of a painter, and a relentless explorer of the human condition. “From a biographer’s point of view she’s a fascinating subject,” Djwa says, “because her creativity is so broadly based … To write just the biography of a poet wouldn’t do justice to her many-faceted character.” Page’s readers know her as a highly visual writer whose work hangs on strong images, who observes carefully and is herself acted upon by what she sees. This ocular facility stretched into other areas: Page began painting while living in Brazil, where her diplomat husband Arthur Irwin was posted, during a period in which “poems did not come easily,” according to Djwa. But her visual imagination began to develop much earlier, while working as a scriptwriter for the National Film Board in Ottawa (then the National Film Commission). Or maybe even before then, while exploring the Prairies on horseback with her father or her friends. Djwa portrays Page as an artist across disciplines, and an apparent master of anything to which she put her hand. She treats Page’s study of Sufism as a form of this promiscuous, borderless creativity. In periods when Page was not writing or painting, especially beginning in the 1970s, she continued to pursue self-discovery through her Sufi study group, as well as through the writings of Gurdjieff and Idries Shah. This, to Djwa, was not a fallow period for Page but rather her relentless creative spirit expressing itself in a new medium.

In the Ideas documentary The White Glass, Page says she is interested only in the broad strokes of a life; Journey With No Maps gives us much, much more than that. The back cover claims it “reads like a novel,” but this is not entirely accurate. A novel might experiment with what could be conveyed in the smallest amount of information possible – this is the seductiveness of good novels, that they lay out a few items, a gesture here, a hat there, and allow us to draw our own conclusions. Journey With No Maps is thick with information: comings and goings, lists of names, letters sent and received, reams of quotations from Page herself to fans, critics, friends, and the mailman. But still, somehow, we are left to draw our own conclusions from this encyclopedia of Page; Djwa refrains, with perhaps an overabundance of tact, from setting in place a real narrative arc. Had she been more selective, focusing on a particular storyline or aspect of Page, the book might have been more novelistic, though less exhaustive. But here all things are important, some things are very important, but no one thing is all-important; there is just a life, in broad and thorough detail. Make of it what you will. mRb

0 Comments