Jean-Claude Germain, the Montreal journalist and playwright, published a very charming book a few years ago entitled Rue Fabre: Centre of the Universe, in which he recalled, among other things, accompanying his father, a distributor of candies and cigarettes, on compelling and sometimes puzzling trips about the city and district.

Germain returns now with Of Jesuits and Bohemians, an equally charming reminiscence of his slightly older youth spent at the long-gone, Jesuit-run Collège Sainte-Marie on Bleury Street in Montreal, and his joyous discovery of sights and sounds just beyond its walls. “How happy we were to find ourselves a few hours later in a bustling, modern thoroughfare,” writes Germain. It was downtown Montreal in the early 1950s, a paradise of big stores and cafés and movie theatres, of nightclubs with display-case photos of women “with their shimmering dresses, their opulent bosoms, their trembling lips, their outrageously made-up eyes, and their blond or jet-black hair.”

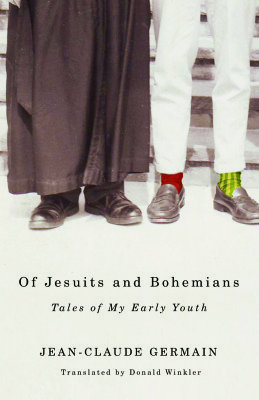

Of Jesuits and Bohemians

Tales of My Early Youth

Jean-Claude Germain

Translated by Donald Winkler

Véhicule Press

$18.00

paper

132pp

9781550653762

Germain went on to a distinguished career in theatre. He wrote plays, encouraged other playwrights as artistic director of the Théâtre d’Aujourd’hui, and taught at the National Theatre School. Clearly, what he discovered in the Gesù theatre that day was worth the two-hour detention he suffered.

Germain’s theatrical imagination was further stimulated by the movies. His family moved to the South Shore, and it happened that the Victoria Theatre in Saint-Lambert was one of those movie theatres where the Quebec law banning kids under age sixteen did not apply. Thus, “going to the pictures gave you the power to become someone else for the distance of a few street corners. Ah! The way it felt to walk the width of the sidewalk after an Errol Flynn pirate film, head high, chin raised, face to the wind, a knife between your teeth, a pistol in one fist, and a drawn sword with its naked blade in the other.”

Here Germain touches on the duality of French culture in North America: homegrown on the one hand and inevitably drawn to the wider stream on the other. Sure, he writes, La famille Plouffe and the rosary over the radio were important, but “the high culture mass on Sunday night was the Ed Sullivan Show, a classy nightclub spectacle with its dog prodigies, jugglers, magicians, acrobats, high-energy comedians, and a cocktail of stardom past, present, and future, from the world of comedy or of song.”

Still, for the young Germain, the greatest enticement was Montreal’s own artistic community: always impoverished, usually friendly, and often ambitious. Its hangouts were refuges – the libraire Tranquille on Sainte-Catherine, the beatnik clubs on lower Clark Street, the Swiss Hut on Sherbrooke – and its stars magnetic. These were the bohemians, a group that included the sculptors Robert Roussil and Armand Vaillancourt (who “dominated the dance floor with the elegance of a Greek god”), the writer Claude Gauvreau, the actor Gilles Latulippe and the artists Ferron, Letendre, Molinari, Pellan, Riopelle.

These were interesting people, doing interesting things: lending a soul to the city, pushing the boundaries of art and society, leading Quebec out of its darkness. Germain writes of them affectionately, and gratefully. mRb

0 Comments