It’s amazing to learn, from this compelling and comprehensive book, that there are as many Americans claiming French-Canadian ancestry today as there are Canadians, about ten million on each side of the border. Those in Canada are descendants of French colonists who settled in the St. Lawrence Valley (and elsewhere) in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Those in the United States are the heirs of nearly a million French-Canadians, mostly from Quebec, who relocated in the period from 1865 to 1930 to work in the shoe factories and paper plants and especially the cotton mills in dozens of New England towns and cities.

It is often not a happy story. The mills were “loud, blazingly hot, humid, and frequently dangerous,” writes David Vermette, a Massachusetts historian and descendant of canadien millworkers. The reception of immigrants in New England was sometimes less than friendly. And the company tenements, where most canadien millworkers lived, were pits of despair and disease so rife with diphtheria and typhoid that a priest complained he “buried more children than he baptized.”

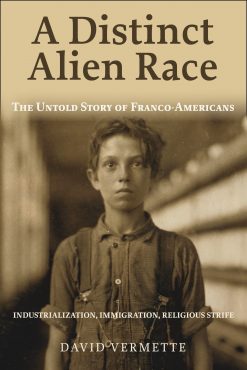

A Distinct Alien Race

The Untold Story of Franco-Americans Industrialization, Immigration, Religious Strife

David Vermette

Baraka Books

$29.95

paper

390pp

9781771861496

Mill owners, who saw French-Canadians as desirable employees, hardworking and docile, with no history of labour organization, actively recruited them. Children as young as ten, inured to labour on their family farms, joined their parents in the mills.

Wages in the form of cash money, however inadequate, were an attraction at a time when Quebec society was practically cash-free. The people back home, Vermette notes, “were unaware that an uncle from the States could flash a gold watch […] and still live in stiflingly overcrowded housing, with inadequate sewerage facilities, poisoned water, and high child mortality.”

French-Canadian enclaves called “Little Canadas” sprang up in many New England towns, meaning that canadienscould move to the United States and be reasonably confident (at least for a couple of generations) of remaining French-speaking and Catholic. At the same time, people leaving for the States often sold off their goods and property to finance the trip, so they had to make a go of it in the United States. There was nothing left in Canada to go back to.

The appalling conditions in mills and tenements were no secret, but (quelle surprise!) government and health officials routinely sided with mill owners and little was done. Heaven bless the occasional crusading journalist who rose to the occasion. The squalor in Brunswick, Maine, thundered Albert Tenney, editor of the Brunswick Telegraph in 1886, “show[s] a degree of brutality almost inconceivable in a civilized community.”

Prominent among the brutes who owned the mills and abused their workers was the Cabot family of Boston, rich from trading slaves and opium, and open to new investment opportunities. (This is the same Cabot family that has summered at La Malbaie, Quebec since the mid-nineteenth century, and created a world-famous garden there.)

Eventually, regulations in New England tightened. The mills relocated to the more laissez-faire US South, and thecanadiens, largely English-speaking by the mid-twentieth century, melded into the American mainstream. Vermette says at the end of this fine book that these now-Franco-Americans “need to find their voice.” And here, I think, he protests too much.

It seems to me that a people who produced a writer as revolutionary as Jack Kerouac, or as successful as Grace (DeRepentigny) Metalious, or as established as Will Durant has found its voice. Kerouac, Metalious, and Durant get short shrift in this book, and there’s no mention at all of Annie Proulx, Paul Theroux, or Madonna, for heaven’s sake, whose mother was a Fortin – all of whom are descendants of New England mill town French-Canadians. It strikes me their voice is loud and clear. mRb

This is a great book and this review is mostly positive.

That said, you totally miss the point of Franco-Americans being inviscible. Madonna? Come on now haha. We get 0 mention in US history and are not fully understood by Canadians. It seems that even after reading the book, you still don’t get it. Time to visit New England and see the invisibility first hand.

Good review, left out is the impact French Canadians have made on other cultures in the United States. A large proportion of the Sioux tribe trace their lineage back to the Amyot/Amiotte family of Ste. Martine, Quebec. Jim Thorpe, the greatest athlete of all-time was the son of Charlotte Vieux/Viau from that great Quebecois family. Big Bat Pourier was the “Adam” of a large group of heartland Native Americans. The list is extensive. Much of it is in danger of being lost as other cultures appropriate the contributions of the Quebecois to United States culture.