People have been writing novels about infidelity for about as long as people have been writing novels. Indeed, within the literary canon – think Anna Karenina, Madame Bovary, or The Great Gatsby – adultery is about as common a subject as an absent father or an unplanned pregnancy. Incidentally, 26 Knots, the debut novel from Montreal- based pediatrician Bindu Suresh, has all three of these things. It wasn’t until after I’d finished reading, however, that I noticed just how much Suresh had packed into such a slight volume.

To call this novel a page-turner is an understatement. Told in short bursts of prose seldom longer than a page, its format is reminiscent of Kim Thúy’s books (Mãn, for example, explores a similar theme). Unlike Mãn, this story heats up quickly – and literally – when two journalists, Argentina-born Araceli and Gaspésien Adrien, meet covering a Montreal fire in early June. Soon, the two are making love on a balcony in the Plateau.

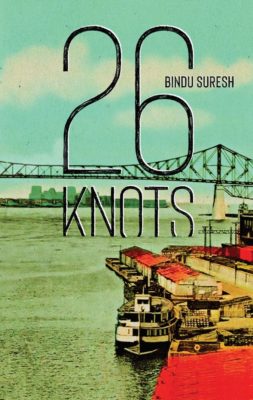

26 Knots

Bindu Suresh

Invisible Publishing

$19.95

paper

152pp

9781988784243

With these four characters given approximately equal real estate, such a short novel could have felt crowded. It doesn’t, thanks to the author’s economic execution. The sparseness of the narrative allows small moments to take on poignancy, as when Adrien, in the early, sleepless throes of a love affair with Pénélope, watches “her close her eyes, for a full two or three seconds, in the middle of a televised interview with the leader of the opposition.” Later, Pénélope experiences a fleeting moment of shame at “having excited two men in one night.” Gabriel feels the definitiveness of his relationship when he at last sets a framed photo of his secret-lover-turned-wife on his desk at work.

At other times, however, I wanted to pause longer before turning the page. The ending, for instance, might have benefitted from additional development. It’s a conclusion that seems inspired by some of the early masterpieces of the adultery genre, and while this reader would have gladly settled for something less dramatic, this book never pretends to be anything other than dramatic. For me, though, the scene’s pace undermines its plausibility.

Aside from a surplus of semi-colons, Suresh’s prose is sumptuous and lyrical. When Adrien dumps her, Araceli feels “love slide through her like a spear of light, like an arrow, as pure and white as moonlight.” Descriptive details are few and far between, but memorable. During the fire, for instance, Araceli and Adrien watch “charred fragments of building chip from the façade, covering the ground before them like a slow and purposeful rain.” Later, a vacation rental in Cuba is described as having a “heavy- smelling garden.”

Admittedly, part of the pleasure of this book is that it’s not a long-term commitment. Unlike Tolstoy’s take on the same subject, it can be read in an hour or two, thanks to its fast-paced plot and fragmented structure. With a healthy dose of drama, it’s a promising summer read. mRb

0 Comments