Leonard Cohen’s first novel, The Favourite Game, published in 1961, is an ode to Montreal, to one’s early twenties, and to friendship, and opens with an epigraph, “As the Mist Leaves No Scar,” a poem of Cohen’s that includes the lines “as many nights endure/ without moon or star/ so will we endure/ when one is gone and far.” Since Cohen’s death in 2016, we have endured, now that he is “gone and far,” by rereading his poetry and novels, listening to his albums, and, with the publication of The Flame, discovering his later writings.

We now have a new book to help us endure: A Ballet of Lepers: A Novel and Stories, edited by Alexandra Pleshoyano. The collection consists of a novella, the Ballet of the title, written in 1957, and short stories, written between 1956 and 1961. As Pleshoyano notes, Cohen’s letters from the period make it clear that he sought to have these works published, and, years later, we are glad to have, as something new, these old words of his.

A Ballet of Lepers McClelland & Stewart

A Novel and Stories

Leonard Cohen

$34.95

cloth

272pp

9780771018145

Cohen is always at his best when he describes the beauty in the ordinary, and in his prose this is often anchored in descriptions of the Montreal of his youth. The stories in this collection, like passages in The Favourite Game, capture the Montreal of sixty years ago. The narrator of “The Jukebox Heart” courts a girl by showing her, as they walk along de la Montagne, “a lovely iron fence which had in its calligraphy silhouettes of swallows, rabbits, and chipmunks.” In this same piece, Cohen’s abiding focus on the seasons continues. A paragraph opens with “the night had been devised by a purist of Montreal autumns.”

Readers who know Cohen’s work will take pleasure in tracing the paths of images and phrasings. In “Trade,” a character named Nancy describes Montreal in wording that Cohen later incorporates, as he does his lines about autumn, in The Favourite Game. This, along with the story “Polly,” serves as a counterpoint to arguments that Cohen’s female characters are thinly drawn stock characters. As well, the leitmotif of lovers looking out a window in the opening lines of “A Week is a Very Long Time” finds a home a few years later in The Favourite Game, and this motif is also echoed earlier in Cohen’s first book of poetry, Let Us Compare Mythologies:

“Had we nothing to prove but love

we might have leaned all night at that window

merely beside each other

watching Peel Street, wrought-iron gates

and weather vanes, black lace of trees

between cautious Victorian silhouettes.”

Along with windows and gates, another example of what can be described as Cohen’s threshold imagery, between the private and the public, is “in city and in forest,” evident in his first album, Songs of Leonard Cohen, and already here in the early writings. Such images, so distinctively part of Cohen’s style, travel with him from poem to prose to song, and as details they linger.

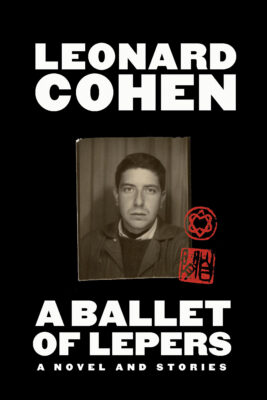

The cover image of the collection is a photobooth picture of Cohen from the 1950s, well-chosen not only because it is contemporaneous with the writing but also because it evokes a passport photograph, which is how this collection functions: as a passport back to a particular time in Montreal’s history, and to a particular moment in the creative output of one of the city’s greatest writers. In The Favourite Game, Lawrence describes his drives to the Laurentians with his friend Krantz, and as he thinks about their friendship and conversations he concludes with “let the words go on like the landscape we’re never driving out of.” With this collection, we continue the drive.mRb

0 Comments