Once, when I was a child, as I struggled to explain to someone why I liked reading novels, I said, “When I’ve done something bad, if I read about someone in a book who’s done it too, I feel better.” Edeet Ravel’s YA novel A Boy Is Not a Ghost (a sequel to 2019’s A Boy Is Not a Bird) would have been a great comfort to me, as it demonstrates that a child’s perception that they have done “something bad” is often an effort to take control when they have none. The novel explores other important topics, like toughness in the face of misery, dependence on the kindness of strangers, and the search for hope and home. The toll that guilt can take even on the most innocent, however, pervades the book from start to finish.

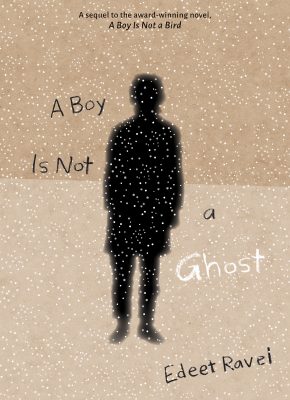

A Boy Is Not a Ghost

Edeet Ravel

Groundwood Books

$16.99

cloth

248pp

9781773064987

Then he tries to decide what is worst about his current, very different, situation: using a public hole in the train floor as a toilet; being stuffed into a tiny carriage with thirty-four others, who have now dwindled to twenty-six, as eight have died; unbearable heat; bugs, including lice… Whether it’s on the train, in the schoolyard in Novosibirsk where they arrive, or in the homes of people who try to offer what very little they have to help Natt survive, the horrors of Stalin’s deportations come alive, and Natt’s coded letters to his red-haired friend, Max, remind us throughout that he is an ordinary boy who used to have an ordinary life.

Yet the story manages to be light-voiced and often sweet. Natt comes off as younger than the teenager he is, mostly because of his frank but delicate narration of the events around him, but also because he is plagued with the kind of irrational guilt that I associate with early childhood. He is haunted by the moment when, given the chance to see his father one last time before he was sent to the Gulag, he turned his face away instead. When his mother is punished for accepting extra food, Natt is convinced that it’s because he didn’t try hard enough to hide his hunger. When he is later exploited by an unscrupulous “friend,” he says, “It was my fault. I didn’t stand up for myself. I didn’t say no.” Natt’s sense of failure regarding the tiny things he thinks he can control demonstrates his deeper helplessness in a way that a more direct narration of that helplessness never could. His need to find someone who can show him that he is a good person surrounded by badness is never articulated, but it might be the most important emotional drive of the book.

A Boy Is Not a Ghost is not an easy story, but it is a quick and compelling read, and will be of interest to young people who would like to know something of the real lives overturned by historical atrocities. Although the journey is terrible, Natt’s company makes it well worth taking.mRb

0 Comments