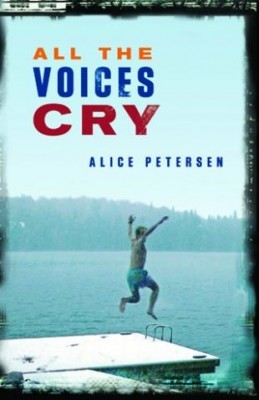

Alice Petersen is the author of the recently published short-story collection All the Voices Cry. Originally from New Zealand, Petersen now lives near Shawinigan, Quebec. She spoke with Katia Grubisic for the Montreal Review of Books. Katia’s review of the collection is featured in the Fall 2012 issue of the mRb.

Katia Grubisic: The stories in All the Voices Cry are not linked in the way some almost-novels / non-novels are, with prismic examinations of one story or character that add up to the sum of their parts. Yet your collection is made up of stepping stones and unexpected juxtapositions, particularly the cluster of stories set in the Mauricie region. Were you not done, as the author, with those characters, that landscape, those odd, artful, and evanescent arrangement of ferns, from an earlier story, that Freya walks by? One result is that the landscape is evoked that much more forcefully; we have walked down that forest path before, we’ve come to that lake every summer…

Alice Petersen: The characters walk through the same landscape, but the way in which they read it, understand it, is inflected by personal preoccupation and personal experience. A bit like life, really.

KG: Place is one of the tastes that stays most strongly in the book. In the stories set in Quebec, the reader can feel that vestigial human presence in the half-colonized wilds – like discovering the foundation of a long-gone house in the woods, or a campfire gone cold. Eerie and comforting at once. In the New Zealand stories, however (and correct me if I’m wrong – this could just be me wanting to read my own nostalgia for a bush-bound childhood into everything), humans, human nature, and social conventions seem more central. Isn’t the opposite the cliché? We’re meant to write about our formative landscapes once we’re away from them?

AP: I never did much writing while I lived in New Zealand. I was busy with my studies, and since it was my own country, I was too close to it to be able to use it as material; it’s hard to make stories up when you are worried about what people will think. With some distance of time and geography I began to look at my country in new ways – I could see it down the wrong end of the telescope, if you like. The distance allows me to work more with cadence of voice or ways of thinking as starter points, rather than specific details.

All The Voices Cry

Alice Petersen

Biblioasis

$19.95

paper

160pp

978-1-926845-52-4

AP: I don’t think of myself in exile. I always meant to return to New Zealand but got married, so I stayed. I used to get terribly homesick, but a geographer helped me to understand that I have two countries, I just visit the other one less frequently than I’d like to. When I finished my academic work I was worried that people would be disappointed in me for not going and seeking out a university job. I was exhausted, and it was the late 1990s and there really weren’t a lot of jobs in my field. I’d also worked on an author who pushed me to the limits of my scholarship. I wondered what it would be like if I took the energy that I’d previously put into criticism, but used it to write my own work. So I had to get over the sense that I might be disappointing people by not going on with an academic career, and I had to get over the sense that everything I did was going to be measured against these impossible yardsticks of the literary canon, because I was full up with the work of great people. I had quotes coming out my ears. I was all the annoying academics that you meet in my stories. I was incapable of meeting the world on its own terms, let alone on my terms, or words. That sounds a bit dramatic. I think was mildly nuts at the time.

And of course, like the art historian who fancies herself as an artist, I had to learn to write from the beginning. So there was a lot and there still is a lot to learn. I managed to change my thinking about the literary canon and turn all those folks into kindly mentors rather than endlessly measuring my own work against what I knew was great and always finding my own attempts poorly wanting. I worked a long time on Gertrude Stein, and I know that if I’d ever knocked on her door and showed her my writing, she would have quickly shuffled me off to talk about needlepoint with Alice B. Toklas – I probably would have enjoyed that as much as anything. But in her current state, Gertrude can’t turn me away, so I am free to learn anything I want to from her example, about working hard and keeping at it, and it’s the same for the others.

Being away from New Zealand helped me to see the country from a distance, helped me to think of it as material rather than a wrap-around lived experience, and being away from academia helped me to think about my writing as a creative pleasure rather than an instant failure. So now, when I visit the country of literature or the country of New Zealand, I visit as a tourist, with that distance and curiosity that is helpful to the imagination.

KG: Just as a writer needs distance and solitude to create a world, many of your characters watch the world go by, or are avatars for your reader to do so, whether it’s an oblique reference to capital-h history in “Neptune’s Necklace” or intimate moments no one else would ever notice in “Scottish Annie.” Gordon in “Through the Gates” (a beautiful story, courageous in its simplicity) wonders whether “the man existed who would be patient enough to lie down and be run over by a glacier.” Yet the enracination I see as the pivot in many of these stories isn’t quite patience; the connections (to place, to other people, even to behaviour or habits) are deep, and maintained, by sheer stubbornness. Are any of the stories in All the Voices Cry an ars poetica for you? A way of watching the world that echoes your writerly perception?

AP: You know, I think the one phrase that comes back to me is something that Freya in the title story says when she talks about “sustaining illusions.” The stubbornness that you identify is perhaps my continued belief in the importance of things, winter hats or sock puppets, pot plants, or the possibility of love – the challenge to make anything important really, in the face of what we know about life. I once read something by a critic who was annoyed that we all go on writing as if Samuel Beckett had not been around, as if he had not brought us his sparseness, his empty communications, his utterances like “they give birth astride of a grave.” By calling them “sustaining illusions,” Freya is saying that despite death, and the brevity of our time here, we do carry on – yes the abyss is there, but if we were always staring down at it, we wouldn’t enjoy the day very much, would we?

0 Comments