Patrick Senécal’s novella, Against God, translated by Governor General’s Award winner Susan Ouriou (Pieces of Me) and Christelle Morelli, describes the spiralling trajectory its protagonist, Sylvain, a man in his midthirties, takes after his wife and two small children are killed in a car accident.

Prior to the death of his family, Sylvain ran a successful sporting goods store, lived in the suburbs, and led a seemingly ordinary, peaceful life. Indeed, the book opens with a telephone conversation wherein all of the family members speak tenderly of how they look forward to seeing one another later that same day. Sylvain’s family does not come home, however. Instead, a couple of cops show up at his door looking at Sylvain “as though they’re carrying the weight of the world on their shoulders.’’

The shock of losing his wife and kids drives Sylvain over the brink. In no time flat, the man is throwing family members into traffic, robbing depanneurs, shooting a priest, and crucifying a young woman to her apartment wall.

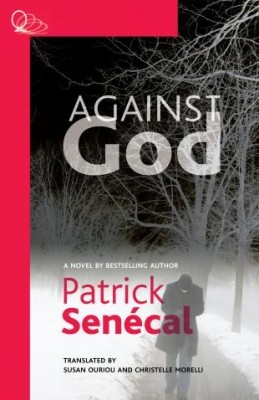

Against God

Patrick Senécal

Translated by Susan Ouriou & Christelle Morelli

Quattro Books

$14.95

paper

107pp

978-1926802787

The novella, written in the second person, uses a single stream-of-consciousness sentence for the span of the novella, and uses periods for dialogue only. Punctuation is otherwise signalled with the use of italics, commas, apostrophes, and question marks. The form no doubt parallels the content. Senécal’s use of the single sentence device may signal that his character’s disorder exists as much outwardly as it does within, and that his derangement knows no end:

… you look at the woman crucified to the wall whose eyes never cease their pleading, you bring your face close to hers, and now you’re no longer crying because your eyes are two craters erupting, desiccating forevermore any future tears, and the harsh caw of your voice rises from the bitterest of chasms, and your words

– Live . . . and suffer.

Unyielding violence can be done beautifully. At the very least it can be a useful plot device. Books like Jerzy Kosiński’s The Painted Bird, Patrick McCabe’s The Butcher Boy, and Gilbert Sorrentino’s Red the Fiend, do it well on an aesthetic level, on a language level. Certainly Against God packs in so much slaughter and mayhem that the story moves at a good, page-turning, and then – and then – and then – clip. But unlike these books, which depict constant, crushing violence with visceral, macabre imagery, the violence in Against God lacks purpose, beauty, or weight. While Sorrentino’s Red the Fiend and McCabe’s The Butcher Boy demonstrate environmental and sociological triggers for violent behaviour, it is uncertain why Sylvain snaps in Against God. Is tragedy enough to trigger a sociopathic break?

Was the love of a good woman all that tied Sylvain to acceptable conduct? And if it was, does that make the character a man, a monster, or a child?

Without touching on these questions, the book’s revenge tactics appear two-dimensional and melodramatic, and they frame Sylvain’s acts within the constraints of a narrow, barely post-catechism worldview. Though perhaps it is such small-minded views of the world that can justify intentional harm against others. mRb

0 Comments