As I read Elizabeth L. Abbott’s An Inner Grace: The Life Story of Dr. Maude Abbott and the Advent of Heart Surgery, I was simultaneously reading Howard Adams’ Prison of Grass: Canada from a Native Point of View. Adams’ book is now almost fifty years old, but when it came out, it rewrote white supremacist narratives about Indigenous governance and the history of nation-building in Canada. The two made unlikely bedfellows, but since Dr. Maude Abbott’s life story is told as though inseparable from the history of early twentieth-century Canada as it established itself as a nation, I found the pairing useful.

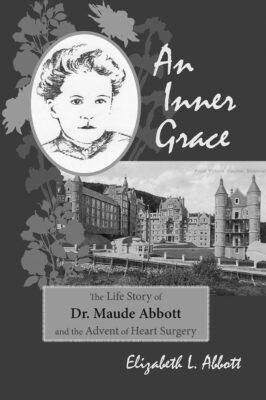

An Inner Grace

The Life Story of Dr. Maude Abbott and the Advent of Heart Surgery

Elizabeth L. Abbott

Corner Studio

$22.95

paper

236pp

9781738897827

An Inner Grace fictionalizes Maude’s life from its earliest days, making clear that she overcame every kind of childhood trauma through determined and joyful brilliance. That she grew up surrounded by the elite and powerful lent her many advantages, but she distinguished herself from even that privileged setting by establishing the dangerous and thrilling precedents that she did. Defying institutional inertia, Maude became the curator of McGill’s medical museum and an assistant professor in its medical faculty. Her most important achievement was the 1936 publication of her Atlas of Congenital Cardiac Disease. A literal manual of the heart, it saved the lives of many children born with cardiac ailments and paved the way for the world’s first heart surgery in 1944, which took place four years after Maude’s death.

Maude defied the bounds set for women at every turn, yet in this recounting of her story, those bounds are re-established with vigour. An Inner Grace is carefully researched and relies heavily on Maude’s own diaries, but it seemed cruel to see this brave woman reduced to her most sentimental outpourings – had Maude been in love with William Osler? Maybe, but would she have wanted me to know? It felt even worse to read mean assessments – whether they were Elizabeth’s or Maude’s, I couldn’t tell – of Maude’s “sinful” love of food, fabric, and fancy things. When Elizabeth describes the special corsets she got fitted and how the general store owner at St. Andrews would patiently watch Maude “draping yards of fabric about herself, shaping it in certain ways to see what magic could be achieved,” I found her not sinful, but delightful and charming. Maude was a woman who was not tied to her time, but this telling of her story shackles her to turn-of-the-century mores.

The same is true of the broader history in which An Inner Grace is set. Elizabeth describes Maude’s life within the grand narratives of Canadian history – the building of the Trans-Canada railway, the tragedies of WWI, the outbreak of WWII – without any awareness of the way contemporary historians have revisited those histories. Adams’ Prison of Grass, however, shows that Sir John A. MacDonald was not only the country’s first Prime Minister, but also the architect of residential schools, of illegal methods to control Indigenous movement on the prairies, and of rebellions in the West. Though many influential people in the East saw no need for the railway, it was part of MacDonald’s grand plan for the country, and Indigenous land tenure, culture, and people were in the way. By fomenting rebellion, MacDonald justified the need for a railway that could rapidly transport military personal and supplies to the unruly West.

It is both a fool’s errand to try to guess what any historic figure would have thought of the period they lived through, and the very task of writers of history, novels, and bibliography. I wondered if Maude, who expressed curiosity and respect for Indigenous medical knowledge, and who lived through the now-forgotten news of MacDonald as a corrupt politician, might have also rejected this version of early Canadian history.

Elizabeth Abbott has published many books in her lifetime, but this one is a particularly close-to-home offering. Dr. Maude Abbott wasn’t born an Abbott, but was given the name as a young child so as to protect her from the shame of her parentage. This means that Elizabeth and Maude are related, but distantly, across generations and familial branches. Published by a local small press, An Inner Grace will be of interest to loved ones in Abbott’s familial line, as well as anyone wanting to get into the petticoats and bonnets of fin de siècle Montreal.mRb

0 Comments