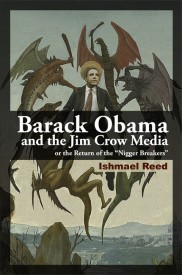

Barack Obama And The Jim Crow Media: The Return Of The Nigger Breakers

Ishmael Reed

Baraka Books

$19.95

paper

256pp

978-0-9812405-7-2

In Reed’s view, the mainstream American media, increasingly dominated by white, corporate elites, often pass biased judgments on President Obama, whom Reed does not hesitate to critique. His book is one way to offer a counterstatement to what can otherwise be racially inflected news accounts lacking the objectivity they claim. As he explains in an interview, contextualizing the politics behind his decision to publish this book: “I want to point out that with the disappearance of black and minority journalists what we have left is an all-white jury that passes judgment not only on blacks in general, black celebrities, black institutions but the President of the United States. It’s like the old Southern all-white jury. And that’s what we have in the sense that the media is Barack Obama’s main opposition. They’re the ones who stirred up this Tea Party thing. The media is out to break Obama.”

Reed begins Barack Obama and the Jim Crow Media by referring to the concept of “nigger breaking,” an activity rooted in slavery. As Reed points out, the Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an iconic slave narrative, contains one of literature’s most powerful analyses of the nigger breaker in the representative of Edward Covey. A poor white sharecropper who breaks the will of rebellious slaves through beatings, overwork, and intimidation, Covey exploits their captive labor before returning them to their legal owners, cured. Reed superimposes this image on the media’s relationship with Barack Obama, which, at the behest of corporate interests, humiliates him both for public consumption and to send a message to other blacks. In doing so, he returns to the crucifixion of African-American public figures, such as Michael Vick, Tiger Woods, Michael Jackson, and Marion Barry; the smugness of the black morality police – including the president and various celebrities, such as Henry Louis Gates and Bill Cosby – who publicly lecture black men on their ethical failings to boost their popularity; and, incorporates autobiographical tidbits on his own struggle against the system. As he asserts: “You can’t get Spike Lee’s film, Miracle at St. Anna’s, about black soldiers saving Italian villages. It’s only showing at 10:30 p.m. in Oakland. . . . You’ve got widespread Negromania going on. Why would the New York Post spend more time in its pages on Tiger Woods than 9/11?”

In fact, Reed insists that it was necessary for him to publish this book in Canada because American publishers were so resistant to its message. And for Reed, who has longstanding ties to Quebec, the decision was an easy one. Robin Philpot, the Montreal-based publisher of Baraka Books, began reading Reed’s prose in the 1980s and admired the latter’s opposition to “United States or North American monoculture.” Believing that Reed would be attracted to Quebec’s distinctive history, Philpot invited Reed to Montreal in the 1990s. The two have maintained a warm relationship over the years; they have met each other’s families, have complementary political temperaments, and have published each other’s work. Reed – who grew up in a working class family in Buffalo, New York, understanding the combined pressures of racism and economic marginalization – considers Quebec a second home.

Ishmael Reed is perhaps best known as the author of such unsparing satires as Mumbo Jumbo (1972), Flight to Canada (1976), and Reckless Eyeballing (1986). Controversial novels that challenge American political tenets and racial and gender pieties, these have guaranteed him a place within the American literary canon. An active champion of the work of other artists and writers, he has received the prestigious Guggenheim Fellowship and the MacArthur “Genius” Award. He has managed to integrate political activism with cultural advocacy, serving as a founding member of the Oakland, California, chapter of pen.

Reed thus brings a certain intellectual and moral authority to his outlook. Yet, caustic and contrarian, he is an intellectual gadfly with a strong libertarian streak. Alternately praised and reviled by both the left and the right, he refuses to squeeze himself into a one-size-fits-all rubric.

This paradox informs his most recent foray into the culture wars. On a topic demanding a sustained, objective treatment, Reed’s book provides an intriguing but highly subjective interpretation of “the media industrial complex” and American values. There are no sacred cows in his pantheon, as some of his chapter titles so evocatively suggest: “Goin’ Old South on Obama: Ma and Pa Clinton Flog Uppity Black Man,” “The Big Let Down: Obama Scolds Black Fathers, Gets Bounce in Polls,” “McCain Gurgles in the Slime.” Those headings alone shimmer with a brilliance at once acerbic and hilarious. But they suggest the problem at the book’s core. Once the initial laughter dies down, one can feel claustrophobically enmeshed in Reed’s dyspeptic observations. It seems possible that Reed is intent on settling old scores – with feminists; black academics and public intellectuals; white liberals; the Irish-American chattering class of celebrity media commentators; and (perhaps most predictably) the Right Wing Media, which morphs into “the establishment media, progressive, right, left and mainstream.”

He contends, offering a rationale for his censure of what he perceives as the status quo: “You put something out there like The Wire, The Bad Lieutenant, Port of Call, where all the drug transactions … take place in the black community like in my neighborhood. And in Port of Call … you have black Americans competing with Senegalese immigrants over the drug trade. I just read that Wells Fargo had to pay $152 million for drug laundering … But they never make a movie about Wells Fargo. It’s all about black folks.”

What works in Barack Obama and the Jim Crow Media, works well. There is a brutal candour in Reed’s argument, which often feels refreshing in light of the euphemisms and platitudes typically expressed in both polite discourse and the media’s self-scrutiny. He writes, for example, on black conservatives: “I’m wondering where the MSNBC and CNN producers get these far-right black people. Does Karl Rove have a secret Maryland laboratory where if one could hurdle a barbed wired fence, one would find a windowless building where inside these black right-wingers are being created in tubes, ready for use by the networks as opinion stand-ins?” Whether or not one agrees with Reed, one can only be entertained by his gleeful barbs and edgy turns-of-phrase. He names names and shames with derision.

And he is unsparing in his appraisal, of both President Obama and the former’s numerous critics. Significantly, he begins the book with a compelling list documenting President Obama’s many accomplishments in his first year of office – too often overlooked by the media in its rush to find fault. But as Reed notes, like Obama “Frederick Douglass turned the table on Edward Covey by whipping him.” He adds with more than a dash of irony, “The present occupant of Edward Covey’s house is Donald Rumsfeld.” mRb

0 Comments