Fifty years after the publication of Leonard Cohen’s groundbreaking and notoriously difficult postmodern novel, poet David McGimpsey reflects on its enduring relationship to the city of Montreal.

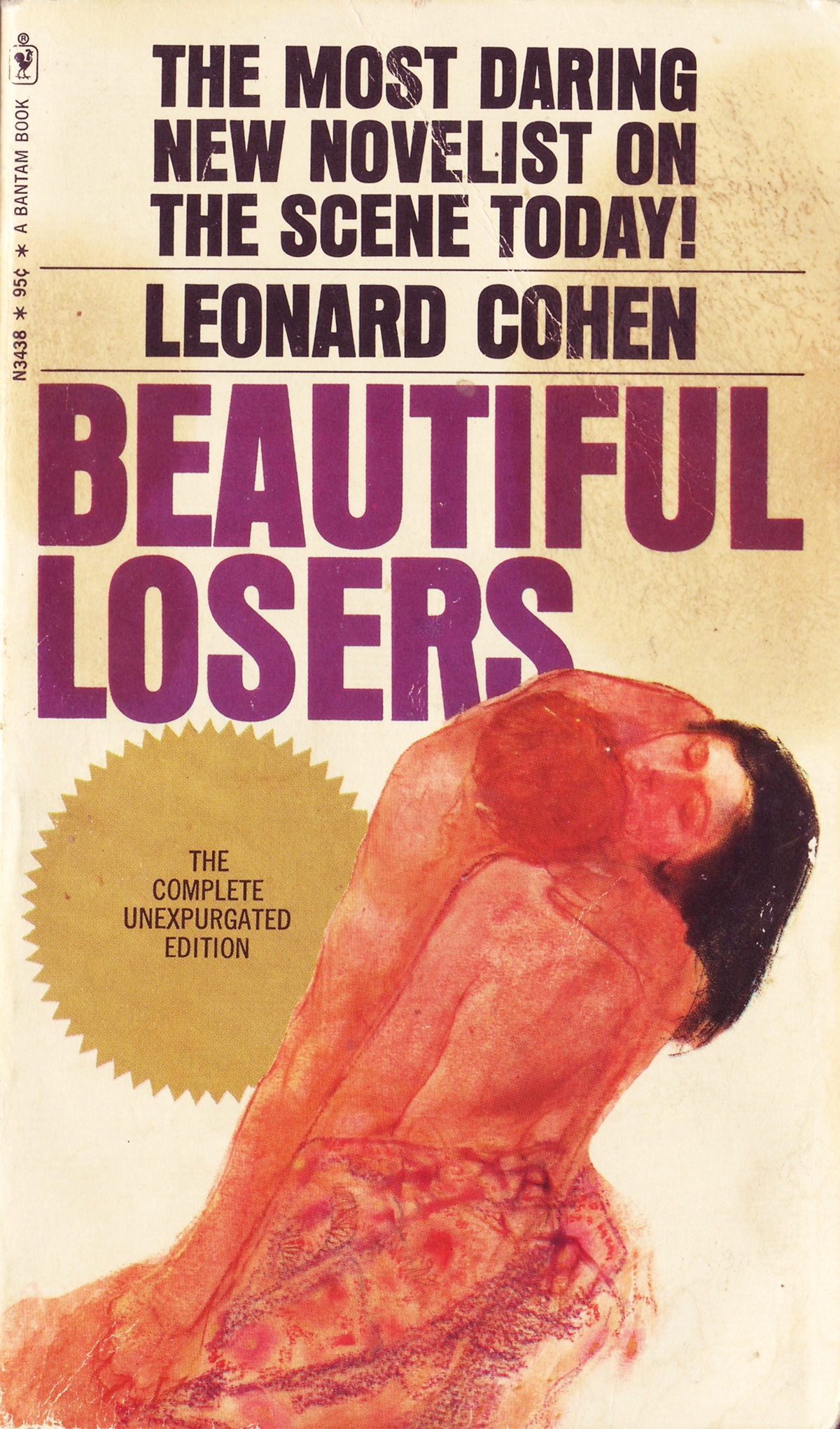

It’s been fifty years since the publication of Beautiful Losers and fifty years since Montreal’s Leonard Cohen last wrote a novel. Cohen is still working (and working well) at the tender age of eighty-two and may surprise us soon with Beautiful Losers II: Electric System Theatre Boogaloo. Of course, after publishing the novel, Cohen set out on his career as the seductive and depresssive pop idol who would become an icon of Montreal every bit as prepossessing as the cross on the mountain or, at least, the Guaranteed Pure Milk bottle. In the fifty years since the publication of Beautiful Losers, one might feel that Montreal has been greatly transformed, what with surviving two referendums, one massive ice storm, and at least ten Stanley Cup parades. But, I can’t be sure that’s true. Looking back today, Beautiful Losers has a striking plus ça change… feel, and while Canadian literary production is particularly good at canonizing the cultural legends it wants, it’s quite refreshing to report that Beautiful Losers remains a really dirty book.

On the face of it, it shouldn’t be so. Saying Beautiful Losers is a novel set in the Montreal of the Quiet Revolution that looks back on the life of seventeenth-century Mohawk saint Kateri Tekakwitha makes it sounds like the Canadian novel par excellence – weaving past into future, bringing the birch forests of our colonial past to the city streets of our alienated today. But, it’s not quite like that. The first person narrator comes out swinging with earnest postmodernist ambition, asking “Catherine Tekakwitha, who are you? Are you (1656–1680)?” – troubling the narrative early with an assertion of the impossibility of reputation and the intercession of competing histories. But, before you get ready to smell the cigarettes that Camus left ashing, the novel starts with its signature riffing, finding phrases like “fuck her on the moon with a steel hourglass up your hole,” which, when you think about it, may be a reasonable metaphor for the hypocritical junctures of history and desire, but not a Farley Mowat flag-waver that’s going to be typified as CanLit.

Beautiful Losers is, in many ways, Cohen’s most accomplished literary work, particularly if we steer away from debating whether or not the lyrics to “In My Secret Life” constitute literature. It is a fully expressive, detailed, researched, sincere novel that takes Cohen’s classic mixing of the sacred and the profane (i.e., is “Hallelujah” a hymn or a song about a break up?) to its greatest limit, all the while frustrating readers not just with its blasé statements which seek to end “genital imperialism” but with its obdurate composition. There are no copies of Beautiful Losers whose pages are so well thumbed they automatically fall open to the sauciest scenes. There are no “saucy scenes” per se and the bulk of the book is mostly a series of near-Joycean gestures, full of wonderful asides and unforgettable poetic drifts (Veil imagery! Sexy saints! We’re all losers!), but a complete disaster if one was expecting, you know, a novel that had pleasure outside the context of an English class or a commemorative retrospective.

Not that Beautiful Losers would be high on any college teacher’s list of Canadian novels to teach (“Excuse me, professor, what does he mean when he says ‘The sexual Hit Parade is written by fathers who shave’?”) any more than it would be chosen as a Canada Reads title or as a title for history’s greatest book recommendation source, Oprah’s Book Club. That consistent discomfort could be Beautiful Losers’ greatest unchanging bragging right: the staunch sense that it exists outside of the ameliorative construct of literature itself and lives in a lumpen pile of sixties and seventies pocket books that were weary of such persistent decency. After all, what could recommend it better than the Globe and Mail’s initial review, which went so far as to tag it with the most finger-wagging of all creative school put-downs, “verbal masturbation”?

It, of course, suits Montreal to be looked at as the source of such wholesome tsk-tsking, as if Beautiful Losers was the pulsing neon of the Club Super Sexe sign, reddening the faces of visitors from Grimsby. But, that is probably more about the idea of Beautiful Losers as a risqué farce and not about Beautiful Losers an earnest, experimental novel. In the book’s memorable graf about Montreal/Quebec, Montreal’s well-worn claim to be the hedonistic antidote to the dull certainties of English Canada is as elemental as the change of seasons:

Spring comes into Québec from the west. […] it sneaks into Québec, into our villages, between our birch trees. In Montréal the cafés, like a bed of tulip bulbs, sprout from their cellars in a display of awnings and chairs. In Montréal spring is like an autopsy. Everyone wants to see the inside of the frozen mammoth. Girls rip off their sleeves and the flesh is sweet and white, like wood under green bark. From the streets a sexual manifesto rises like an inflating tire, “The winter has not killed us again!”

The Cohenesque paradox, where every articulation of sacred longing and historical definition will inexorably be paired with the matters of bowel movements and erections, is, after all, a rather profound paradox of life, whether you live in Montreal, Toronto, or Burnaby for that matter. Beautiful Losers is frequently profound, larded with pausing speculations on death and despair, sexuality and art. As it is not erotic, or orientated to sex-comedy resolution, its precise language still represents a challenge to those who express a desire for honest discourse but still demand coded euphemism. But, for Cohen, the specific words and phrases are an important part of the novel’s dare-to concept of liberation. Considering all the recent Internet hub-bub about the use of the words crap and orgasm in a short story submitted to The Walrus, what indeed would one make of Leonard Cohen’s use of girlcock and cuntflower?

The narrator of Beautiful Losers poetically boasts “I’m tired of facts, I’m tired of speculations, I want to be consumed by unreason. I want to be swept along.” This, too, is the dream of Montreal, even fifty years later – that weariness with our divisive history will lead to moments of what Cohen, in his poem “French and English,” suggests is a “mother tongue” that exists beyond the view of “dead-hearted turds of particular speech.” The threats of revolution in the Montreal of the novel (“Action was suddenly in the streets! They could all sense it as they closed in on the Main: something was happening in Montréal history!”) are far less compelling than a competing song by the great Ray Charles.

Beautiful Losers is set in Montreal but it is not the vivid Montreal of Mordecai Richler – not that his Montreal is any less fictional. But, in its “seedy elegance,” to borrow a phrase from poet Louis MacNeice, it remains a gloriously unteachable, difficult-to-read and problematic text that, perhaps owing to its reputation as an eye-poker, is as neglected today as it was back when Lester Pearson was Prime Minister (“Why can’t I memorize baseball statistics like the Prime Minister?”) and Leonard Cohen decided that singing was his best bet. Where it remains a classic Montreal book, perhaps, is in its spirit of unecstatic bodily pleasure and debauched defiance, like drinking dépanneur wine in the park or smoking beside a swimming pool. mRb

Cool to find this article eight years on! I just finished reading this book and was overall… unmoved?… by it as a whole but really loved some of the passages and his innate sense of poetry and perspective. That being said, I don’t think many of the genius single lines ended up making the overall arc any better, but reading your article definitely applied some perspective that I tried to consider while reading it. Thanks for putting in the time! Your words were super insightful.