There are two kinds of people in this world, as the saying goes. Michael DeForge uses this premise, normally the setup for a joke, to engage in some nimble psychedelic riffing with results more bleak than funny. Ostensibly a coming-of-age parable, Big Kids quickly unfurls into strangeness and unfamiliarity, gesturing toward an allegory that never quite materializes, and finally leaving readers in a narrative hinterland with no epiphany or punchline in sight. Which is to say: it is a triumph of honesty and bravery.

Over the past half-decade, DeForge’s work has become more complex and his audience broader, largely due to a rigorous work ethic. In addition to dozens of online and print comics and illustration commissions, he’s a designer on the much-loved cartoon Adventure Time and a fixture at the Toronto Comic Arts Festival. Just shy of thirty, DeForge is part of a generation for whom the lines between mainstream and underground in the art world are not so rigid and stratifying, likely to be as fluent in the line work of Jack Kirby as that of R. Crumb, at home within the iconography of Japanese manga and French bandes dessinées as much as the Sunday funnies. In a short amount of time, DeForge has cultivated a style that seems at once a synthesis of many traditions and a wholly original voice, comics that pulse with the impeccable timing and expressive minimalism of Peanuts while also conjuring the opaque otherworldliness and drifting dream logic of Jim Woodring’s “Frank” stories.

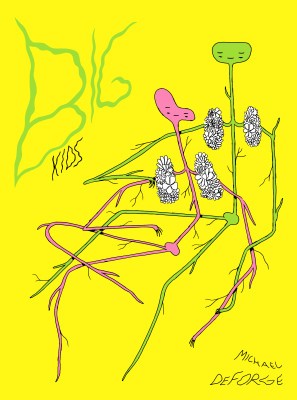

Big Kids

Michael DeForge

Drawn & Quarterly

$19.95

cloth

96pp

9781770462243

While there’s a sense of openness and playfulness that comes from the loose, unmoored metaphor, Big Kids also flourishes under its self-imposed formal restraints. The high contrast, high chroma colour palette radiates with latent energy, intensifying the empathy and emotional depth of the artwork while expanding and contracting in tandem with the story’s changes in mood – apparent, for example, in the differences between the claustrophobic basement setting of the book’s opening pages and the swimming scenes later on. The minimal approach to figuration and page layout move the narrative along almost breezily, in spite of its emotional and psychological entanglements. DeForge’s incredible control over rhythm and timing provides for a limpid, spirited traversal through deeply surrealistic territory.

It’s this compelling rhythm that perhaps provides the strongest sense of resolution by the story’s end, which arrives swiftly and without much conclusion in terms of plot. This doesn’t feel so much like the rug being pulled out, however; if anything, Big Kids seems courageous in its attempt to stare its subject matter in the face and not know what to make of it. Sometimes, we simply feel different and don’t know why, and like big kids, can do nothing but try to bear the weight of the change. mRb

0 Comments