“Everything happens twice,” Tawhida Tanya Evanson tells me, over Zoom, on a bright January day. She doesn’t mean it literally, not exactly. She is referencing William S. Burroughs (who, she notes, was not a good guy at all, but had some interesting ideas). The concept is that particular types of occurrences often happen in twos. “If you miss something once, you might miss it the second time,” Evanson explains. “So, you really have to pay attention, because the future is on the peripheries of your vision. If you pay attention, you can see it coming… But if you don’t notice the experience the first time, you’ll miss it the second time.” Book of Wings, Evanson’s debut novel, puts this concept to powerful use.

The story follows Maya, a Black woman in her late twenties, as she struggles to come to terms with the sudden departure of her lover, Shams, who leaves her without explanation while they are travelling the world together. Unmoored and reeling, Maya flees France, the location of her abandonment, and travels by sea to Morocco. As she moves through that country, from the blue-washed buildings of Chefchaouen to Rabat, from Marrakesh to the fort at Essaouira to the Atlas Mountains, she encounters people, architectures, landscapes, and rituals that awaken her to the fact of her diasporic return, amid heartbreak.

Book of Wings

Tawhida Tanya Evanson

Esplanade Books

$19.95

paper

150pp

9781550655643

Maya’s encounters with strangers, and her own inner laments and incantations, recur throughout the book, turning back on themselves deftly, with slight changes each time, so that even as the narrative seems circular, it is in fact evolving. “O Ancestors, where are your ceremonies? Please, I need them now.” Maya repeats this plea several times, and although she is never answered directly, her growing ability to notice the world around her as she travels provides her with the ceremonies that she needs to move through her devastation.

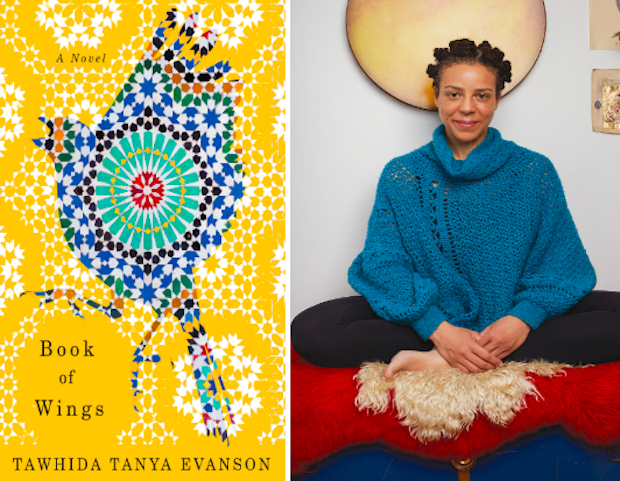

Evanson is a seasoned poet, spoken word performer, and oral storyteller, and her craft is evident in this first work of prose fiction. She is also a dervish – a student of Sufism, a mystical form of Islam, whose most commonly recognized practice is that of whirling meditation. Aspects of ritual are woven into the form and spirit of Book of Wings: “Travel is a good ritual, like prayer,” the narrator declares. “Rituals are reminders. Our movement from gross to subtle.” Reading and writing are rituals too, and it’s not a coincidence that Maya is herself a writer, eventually seeking refuge from the vulnerabilities of solo travel to enter a turbulent affair with Matthieu, another writer, whose rituals she mirrors for a time.

Every so often, Maya hears a mysterious “voice from the other side of the story.” Evanson wisely chooses not to explain much to the reader in these instances. It is important that the writing maintain some mystery, without being too opaque, she tells me. She does give me some hints, however: “[The voice] opens a door to the invisible. We don’t necessarily have all the answers, but it can be interesting to just open the door, to see what’s on the other side of that threshold for you, as a reader, having this experience alongside the character. What do you see on the other side of the door, and what does it mean for you?”

Just as the reader gains awareness of the various hidden layers of the story, Maya becomes conscious of herself and her own patterns of relating to others and the world, even though she has to descend into psychic chaos in order to do so. In the depths of despair, feeling “cursed,” Maya is reminded of the voice from the other side, which sang “La Alla LaLa” to her early in her journey – “one of the songs that the West African ancestors brought through the wretched Middle Passage to enslavement in the Caribbean.” Now, in Morocco, she hears “La ilaha illallah” over and over again, a sacred Arabic phrase which is part of the call to prayer.

She eventually invokes this phrase to help another, chanting it as she works to calm Matthieu when he experiences a psychotic break. Evanson tells me that this is a critical moment in Maya’s spiritual and personal development, that she now understands that prayer is not merely a set of words, embodied as “activated service for another human being, so that the prayer becomes real, something in the body that can be used for healing of the self or of someone else.”

As much as Book of Wings is an engaging story of psychic transformation, it is also deeply rooted in sensorial experience, which saves it from slipping into the vagueness or loftiness that can sometimes hamper tales of spiritual awakening. Evanson’s poetic brilliance casts Maya’s interior landscape against vivid, exhilarating descriptions of the external landscapes she travels through, as well as the particular beauty of each person she encounters, whether that person is welcoming or catcalling her in the street. In Paris, right after Shams abandons her, she is overcome by nausea: “Guts gathered mid-chest, a yellow fist, heavy as a punched sun.”

Despite the physical ailments that plague Maya as she struggles through her pain, her state of loss attunes her to the glorious detail of her surroundings. In Chefchaouen, “slippery cobblestones lend themselves well to a fallen glance from an indigo man in a snow white djellaba.” In a square in Marrakesh: “Burnt pigeon feathers, clay, cumin, chilli, rose and white smoke intoxicated me.” In a village in the High Atlas Mountains: “A heap of fresh spearmint was pushed aside and then slim shards of sugar were cut by cutlass from a crystalized loaf. […] We drank and ate crusty homemade khubz dipped in nutty argan oil.” Evanson’s writing is so evocative in these passages, surefooted even as Maya is lost and stumbling, guiding the story to a distant point, where an alignment of body and spirit might be possible.

Evanson, a full-time artist since 2012, is jubilant that she managed to complete this particular project, which challenged and deepened her approach to storytelling. “I’m happy that this one came out, because it was the most urgent,” she says. But that doesn’t mean she’s taking a break anytime soon. She is currently working on a spoken word project that will be presented as a film, in collaboration with local artists and musicians, with a focus on aging and the Anthropocene – the symbiosis of the human body and the planetary body. And she has another project brewing to follow that one. “I don’t take a vacation because, why?” she laughs. “From what? Art? Impossible!” mRb

Very interesting review; can’t wait to get the book.

Carole TenBrink