When you open Boundless, a new comic book of short stories by Jillian Tamaki, you have to turn the book sideways to read its first story – “World Class City.” The sparse text, a couple of sentences per page, punctuates the large illustrations that take up the whole two-page spread and leak into the next page as one long continuous image, evoking the passage of time. It’s an unsettling effect, if only because of the subtle discomfort of turning the book. This story – more like a prose poem, really – is an ode to a city that may or may not exist. Is it real or Utopia? Is it memory or fantasy?

This uncertainty permeates the entire book as Tamaki (who has, among her accolades, two Ignatz Awards, an Eisner Award, and a Governor General’s Award) explores narrative devices that emphasize a certain ambivalence, a loss of control. The strategy is suitable for the themes that slowly take form in the stories: conscience, connection, identity, isolation.

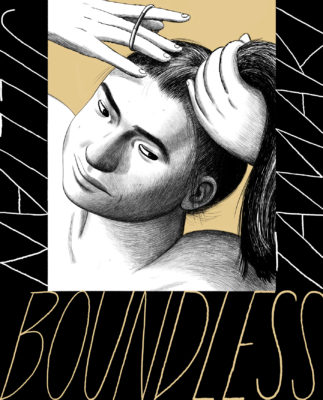

Boundless

Jillian Tamaki

Drawn & Quarterly

$27.95

paper

248pp

9781770462878

For example, in “1.Jenny,” Jenny becomes obsessed with the “mirror Facebook,” an alternate social media site with parallel universe profiles. She checks her alternate self constantly and is troubled by her own unexpected reactions to her double’s life events. When the virtual Jenny has a romantic upset, the main Jenny “felt victorious. Also terrible – she was well aware that her delight equated 1.Jenny’s misery. That made her bad.”

In “Half-Life,” Helen starts to shrink until eventually she almost disappears. The illustrations, in tones of black and blue ink, have an intimate quality to them, a children’s book nostalgia. Even when microscopic, Helen has self-doubt: “I wonder if it’s my own mind playing tricks.”

Tamaki delves into these stories with remarkable generosity. The examination of the uncertainty of the psyche – so present that it invades bodies – and human desire for connection rings authentic in the book’s naturalistic tone and fantastical scenarios. This authenticity gives common thread to Tamaki’s wide experimentation with several genres and art styles. Going from magical realism to faux- memoir, from the quiet minimalism of “Bedbug” to the ambition of the sci-fi-ish “SexCoven,” Tamaki shows extraordinary versatility in her narrative and her art. She can use a sketchy style as convincingly as a finer and cleaner line, always keeping the strokes loose and spontaneous, and the facial and body expressions vivid and playful. The human figures, frequently in a state of metaphysical denial or deprivation, sometimes vanish, behind plants, in movement, in water. Her use of colour is minimal, austere, which is to the benefit of these often-sombre narratives.

Nothing is overly dramatic in these quiet, melancholic stories. Even queerness is depicted as simply existing, without being embroiled in dramatic homophobia or coming-out plots. Yet there is a constant tension, as if to say, “reality is fragile.” There is much doubting and questioning, and the characters keep affirming something just to deny it immediately after. Permanence is just an illusion. And, fittingly, there is never a conclusion, a definite outcome, not even a lesson learned. Only a slightly abrupt fade out. mRb

0 Comments