Claudine Dumont’s Captive is animated by the idea of power, and how quickly it can be gained or lost. When Emma, the novel’s first-person narrator, is abducted from her bedroom by a group of masked assailants and awakens in a locked room, she is quickly reduced to a state of helplessness and terror. Her disempowerment is heightened by the enigmas surrounding her captivity: there is no apparent motive for her kidnapping, and she has no interaction with her captors. As readers are presented with sparse, carefully curated details about Emma’s life prior to her abduction, it becomes unclear to what extent her isolation, and the numbing routine she develops to cope with it, truly represent a departure from her previous life. It seems that she was primarily a passive observer in life as well, with minimal social interactions and a reliance on alcohol to distract her from the bleak monotony of her days.

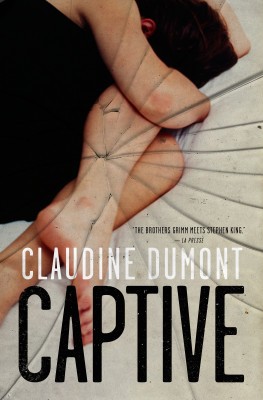

Captive

Claudine Dumont

Translated by David Scott Hamilton

House of Anansi Press

$22.95

paper

200pp

9781487000516

The plot twists that follow in the remaining pages of this slim text continuously renegotiate the balance of power between individuals and their seemingly overwhelming circumstances. The jarring final revelation, in particular, undermines everything that has gone before it. The novel’s form, as well as its content, forces readers to confront their own impotence within a narrative that rarely offers the relief of a logical explanation. Dumont’s writing, well served by David Scott Hamilton’s elegant translation, mirrors the surgical precision of Emma and Julian’s abductors. Sentences are sharp and pointed. Generally minimalist in her style, Dumont strategically deploys a powerful ability to evoke visceral physical realities, such as a lengthy and stomach-churningly detailed description of Emma administering a blood transfusion to Julian.

Lacking the reassuring orientation of chapter divisions, the novel consists instead of sections of varying length demarcated by blank space before the next section begins on a new page. The disorienting use of white space throughout the novel becomes a stark visual reminder of the incoherent experience of time and space for Emma, who is unable to calculate the duration of her imprisonment and loses all visual markers whenever her captors choose to extinguish the lights in her cell.

As a study in suspense, Captive is a page-turner, and its diminutive length makes it all the more likely to be devoured in a single sitting. What causes the novel to linger in a reader’s memory, however, is less the details of the two characters’ experiences than the vivid evocation of being simultaneously a privileged voyeur and forced to share in Emma’s vulnerability because of a lack of signposts about the narrative’s ultimate aim. The limited amount of narrative resolution on offer at the novel’s end may well provoke frustration. On the whole, however, Captive does a masterful job of suggesting that extreme confrontation with a loss of agency can generate provocative questions about the extent to which anyone is ever in control. mRb

0 Comments