W

e’ve all heard the adage about one person’s trash. For comic artist Cesario Lavery, a discarded book found by chance on a winter walk turned out to be not only treasure, but a doorway opening onto a series of intertwining paths through the past, present, and future.The book in question is a collection of writing by Franz Kafka, the much-mythologized Jewish Czech author. Lavery finds it in a Little Free Library and is immediately pulled in, being both a Kafkahead and an inveterate collector of compelling garbage. It’s not just that the book is by one of Lavery’s literary touchstones; it’s also been heavily (lovingly?) annotated and stuffed with clippings – clearly the work of a kindred spirit. The book plate says the previous owner’s name is HCF Shatan, and the flame of Lavery’s obsession is lit. Who was HCF Shatan? The answer takes the narrator from socialist protests in 1920s Poland to the SS Estonia to a 1970s therapeutic “rap session” for Vietnam vets, and into Lavery’s own family history.

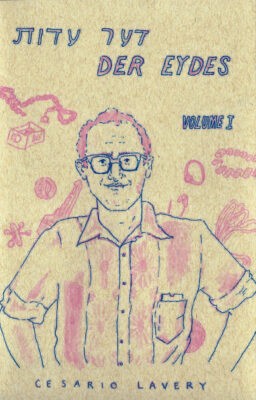

Lavery chronicles the twists and turns of his search for traces of Shatan in Der Eydes (Yiddish for “the witness”), a serialized comic that’s equal parts amateur detective story, family epic, and meditation on trauma, ancestry, and memory. If this sounds like a lot of ground to cover in two slim chapbooks, that’s because it is. Der Eydes is an ambitious project in an unassuming container, and one that’s still, literally, a work in progress. The first two issues have been completed and printed, with a third on the way this summer, and another three volumes to come.

Der Eydes Volume I & II Self-published

Cesario Lavery

Vol. I $10, Vol. II $15

paper

Vol. I 40pp, Vol. II 70pp

For Lavery, comics was a natural outlet for Der Eydes, partly because of the medium’s capacity for unconventional and multilayered storytelling. He has a knack for making the text and images harmonize rather than play the same tune. “I want [the images and the text] to be kind of dancing with each other a little bit,” Lavery says. “And there are times where they’re touching more, and there are times where they aren’t. And I love that comics give you that ability to do that push and pull. And that ability to reference something without directly referencing it, or to recall something from before, in a quiet way. Or a loud way.” In one spread, the narrator muses: “Perhaps you are familiar with the feeling of being newly in love, when everything in the world bears the face of the beloved…” As Lavery walks through winter streets, greets a family, pushes a child on a swing-set, ephemeral pink pages float in the air around him.

It’s perhaps unusual to write about an unfinished work, because at this point we can’t quite see the final picture, the tapestry woven from the threads. But the serialized format has precedence, not only in the newspaper funny pages but in novels like George Eliot’s Daniel Deronda, which Lavery names as a favourite, and in much literature of the Jewish diaspora. “I’ve learned that a lot of Yiddish writers in Montreal, and in North America in general, serialized their stories in Yiddish newspapers,” Lavery says. “So it seems like a fitting way to continue that tradition.”

One thread touches on Lavery’s own family story. Young Lavery, here a child in sock feet, sits on a stoop facing a garden, his father sipping a beer beside him. The child asks, “Where’s your mommy and daddy?” Lavery’s father answers, after a pause, “I don’t have those. You know I was raised by my granny.” It’s a scene full of silence, the silence of a longing that can’t yet be articulated. “Lineage, where we come from, has always been deeply interesting to me,” Lavery says, “in part because there’s been a lot of mystery about it in my family. And whether we know our ancestors are not, there’s so much influence that they exert over story.” Lavery’s father becomes a key ally in the search for Shatan, partly because his inquiries into his own ancestry have made him an adept genealogical researcher.

The weight of absence runs beneath many of the comic’s threads: a yearning for something that’s not quite gone, but that has passed beyond the horizon, out of view. Despite Shatan’s psychiatric breakthroughs, his name is not well-known in therapeutic circles. His mother Mirl’s poetry is written only in Yiddish, a language whose native speakers number fewer every year. An underlying question of Der Eydes is: why are some things remembered, and others lost? Much of it has to do with the stories taking place outside of the usual mechanisms through which culture and stories are enshrined. “Any kind of outsider or historically oppressed community will have this totally different way of preserving stories,” Lavery says. “And these ways can be very valuable, and very beautiful. But they also risk being lost.”

While Kafka is the sort of accidental matchmaker of Der Eydes, bringing Shatan and Lavery together, he hasn’t fully made himself known in the story yet. That thread, Lavery assures me, is for Volume III. Nonetheless, the writer hovers over the narrative thematically. “There’s this cultural legend of Kafka that’s about alienation and isolation and the grotesque and being unlovable,” Lavery notes. “But my thesis is that Kafka was actually very exceptionally well loved. This friendship that he had with Max Brod [the writer and executor of Kafka’s literary estate] was one of deep seeing and deep championing and love.”

That notion of seeing, witnessing, is what gives the project its name. “I was thinking about the idea of Max Brod as the witness to Kafka’s work,” he says. “Work that, without that witness, wouldn’t have come to light. And whether or not this is self-aggrandizing – everyone else can decide – I want in telling [Shatan’s] story, and also in telling my own family story, to act as the sort of Max Brod, witnessing and shedding light on somebody else’s story. For the very simple fact that I want this person’s story recognized and seen, because it’s so good.”

As much as loss, grief, and longing permeate the story, so too do chance, luck, and the joy of connection and discovery. “For whatever reason, whether it was pure chance, or if it was a book descended from the heavens specifically to be in my hands,” Lavery says, “I’m very glad that I found that book.”mRb

I have a collection of Yiddish books, records and CD’s. Any suggestions of where I can donate them?

Looking into it, will get back to you!

You can check out the Yiddish Book Center in Ann Arbor,

https://www.yiddishbookcenter.org/collections/digital-yiddish-library/how-donate-books