Chez L’arabe, the debut short story collection of National Post columnist Mireille Silcoff, establishes its homegrown credentials early on. Not two pages in, readers will encounter Mount Royal, chemin de la Côte-des-Neiges, potholes, and the narrator’s assumption that “all Montreal Arabs [are] Lebanese,” a throwaway line designed to set up a not-so-surprising revelation about the national origin of two minor characters. (Silcoff is not overly concerned with her characters’ innermost thoughts being politically correct – in fact, at moments, she seems to relish their very incorrectness.)

Montreal provides a rich setting for Silcoff, and the city – as experienced by Anglophone or bilingual upper-middle-class Jews, especially – is deftly portrayed. Her keen observations of her fellow citadins and what makes them tick, entitle Silcoff’s contribution to a place in the long line of skilled authors who have paid tribute to la belle ville. Themes of marital dissatisfaction, professional limbo, illness, and strained relations between parents and children loom large, casting distinctive shadows over each of the eight stories. Silcoff’s foray into fiction, preceded by three non-fiction books, succeeds where many other first short story collections fail: it manages to showcase an adept variation in voice, tone, and content, but it also comes together as a cohesive whole.

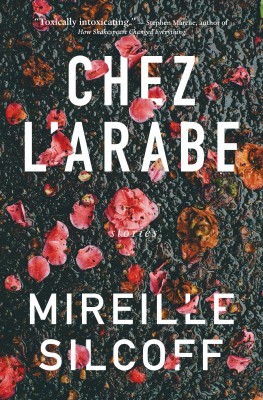

Chez L’arabe

Mireille Silcoff

House of Anansi Press

$18.95

paper, ebook

216pp

Unsatisfying, too, is her drafting of two secondary characters, Mohammed and Samira, who are nearly voiceless (quite literally, in the case of the latter). This slight might not have been so glaring were it not for the lamentable choice of the collection’s titular story. The depictions of the only Muslims (and would-be Arabs) in Chez L’arabe are two-dimensional, and it seems that the sole purpose of these characters is to serve as a facile foil – a springboard for half-hearted, familiar vexations on the status of relations between Jews and Muslims in Montreal.

Still, it is possible to take umbrage with this kernel in Silcoff’s collection while otherwise finding it a well-crafted, engrossing, and highly readable debut. Silcoff has a talent for description. Her neat turns of phrase are bound to make the writer in every reader a touch jealous for not having thought of it first: an ancient car’s “filigree of flaking rust”; squirrels traversing “corrugated trunks”; the narrator’s brain sizzles, “frying synapses like tiny shrivelling smelts.” It is unfortunate, however, that the first two visuals were allowed to be repeated a scant few dozen pages after they first appear.

That said, another form of repetition works very well. Captivating recurring details are laced throughout the stories: Edwardian houses, books propped up on nappers’ chests, small dead animals, meditation and Buddhist principles, attention to the details of domesticity in decor and food and hosting. The reader grasps at these subtle clues and attempts vainly but enjoyably to piece together the ways one story might be connected to another. Along the way, spines may stiffen at a pothole or two, but it’s a ride well worth taking with Silcoff behind the wheel. mRb

0 Comments