The first novel by Ioana Georgescu to be translated into English, Daughter of Here spans decades and continents with a graceful ease. Anchored in time by the events of Tahrir Square in 2011, the narration moves fluidly through time, while being propelled toward this revolutionary moment. As Dolores and her daughter, Mo, await the arrival of Mo’s father Célestin, a war photographer, she writes down bits and pieces of her past, as well as the sights and sounds that they are witnessing from their apartment, located near the infamous square.

Like the author, Dolores is a visual artist, whose work takes her around the world. Throughout the book, looking outward is inextricably tied to the notion of looking inward – observation as the other side of intimacy. Any window looking out on the world becomes a “room of one’s own” that the narrator learns to inhabit from her mother, and which she will pass down to Mo.

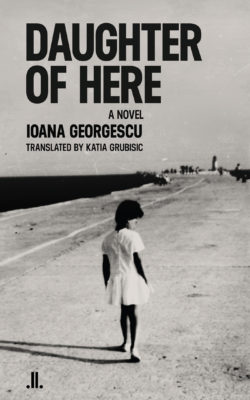

Daughter of Here

Ioana Georgescu

Linda Leith Publishing

$21.95

paper

220pp

9781773900681

The window’s closely related form is the photograph, a narrative device that continually links past to present and acts as storyteller. Célestin’s war photographs tell of brutal conflicts that cost many lives, while Dolores’s black-and-white images of childhood tell quiet stories laced with the tension of their time. Like the window, they are passed on through generations of women, and they serve not only to capture moments, but also to offer conversation pieces and starting points.

The book also offers some wonderful reflections on the process of creative work:

I am contemplative, an exquisite state. I stare out along the jagged horizon line. I’ve finally understood that this idleness is not unproductive. On the contrary, this is when work does the work.

In this impressive translation by writer and translator Katia Grubisic, the prose comes through with clarity, lean and straightforward. Dolores embraces the wandering poetry of the everyday, but in a rhythm that drives ever forward: “The bawaab and his family live above me, and leaks from the caretaker’s home have stained the ceiling. It looks like an old map, separating two worlds superimposed.”

At times, the novel recalls Elena Ferrante, especially when its narrator delves into intellectual intimacy, exposing thoughts, fears, and triumphs with careful ease. She has a similar way of drifting seamlessly between childhood, memories of past loves, and aching tenderness for her daughter. Yet other moments recall the dizzying country-hopping cosmopolitanism of Mavis Gallant’s short stories, particularly in Georgescu’s keen eye for character. Much space is devoted to the quirks of artist friends and chance encounters with locals.

Dolores has a way of being embraced with ease by everyone, while also keeping the distance required for observation. This paradoxical state is, of course, the mark of an artist. It is also what lends the book its title. Dolores is a daughter of everywhere she goes, at once American and Romanian, Egyptian and Japanese. She finds footing in the multilingual, multinational conversations that fill her memories. But her multilayered identity is also a reminder of the many lives that are possible over the span of a lifetime, and over the course of generations. As Dolores reflects: “I am the daughter of the woman in the window; I am the girl and the woman on the jetty, who loved the sea, and who loved to fly and to dream.” mRb

0 Comments