Didier Leclair’s novel Toronto, I Love You is a portrait of a multicultural society, with all its twists and turns. Told from the perspective of Raymond Dossougbé, it delves into the challenges of a newly arrived immigrant to the city. Swept up in his surroundings, he spends most of the book trying to understand both the affinities and the fault lines that lie along every step of the journey.

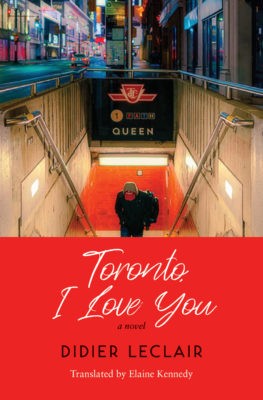

Toronto, I Love You Mawenzi House

Didier Leclair

Translated by Elaine Kennedy

$20.95

paper

176pp

9781774150665

While waiting, Raymond also bides his time by listening to the revolutionary politics of Koffi, whose room is filled with images of Pan-African heroes such as Malcolm X, Martin Luther King Jr., Toussaint Louverture, and Patrice Lumumba, and trying to connect with his roommates Bob and Joseph. But an unconditionally Pan-African welcome is not in store for Raymond, whose identity brings sharp tension into the flat: “I felt like the sole lost link in a chain forever broken. The lyrics of the song evoked the suffering of the slaves and the courage of contemporary blacks. Bob and Joseph were conveying their emotions to me, arousing a feeling of guilt in me, even though I had the same colour of skin. It showed me that I couldn’t identify with them.”

When not joking with his roommates or biting his tongue to keep from entering political discussions, he is swept up in the adventurous life of Maria, a second-generation Portuguese-Torontonian who offers a unique portrait of cultural identity that fascinates Raymond: “To find harmony in her life, she was trying to reconcile her freedom as a woman with the values of her family’s homeland. She was both of her generation in North America and of another in Europe. Her harmony had to be contradictory to exist.”

At his best, Leclair’s Raymond offers cutting remarks that are yet infused with a kind of tenderness for those around him. Of an older companion back in Benin, he remarks that this former revolutionary “represented, in and of himself, an Africa that had been piously educated, that had revolted, and that was now irrelevant. During his monologues, I could easily imagine him discussing politics with the great leaders of a bygone era.”

Aside from sharp and pithy insights, the quality of the prose itself provides much of the book’s pleasure, translated with sensitivity by Elaine Kennedy. The descriptions of the city in particular ascend from the page. On seeing a small patch devoid of skyscrapers, Raymond declares, “The open space there revealed a sky as bare as the head of a crownless king.” The subway alone provides a seemingly inexhaustible source of poetry, described as a “metallic snake that chases its own shadow within the bowels of the earth,” and a “prince of darkness” filled with “human tentacles” that come out at each stop.

In this deeply nuanced portrait of society, Leclair’s Raymond, along with the acquaintances, friends, strangers, and sometimes reluctant companions that people his days, offers this key insight: that there is no singular immigrant experience, but rather a multiplicity of voices, all offering their unique and precious view on the city itself, on their life in Canada, and on their relationship to their homeland.mRb

0 Comments