Thinking about Paris often leads to overworked and clichéd images of lights and romance, thanks to the city’s countless appearances in literary and cinematic works. But, in his second novel, Dirty Feet, Togo-born Quebec author Edem Awumey overlooks the much-explored image of Paris as the luxurious and vibrant cultural centre in favour of the city’s dark side.

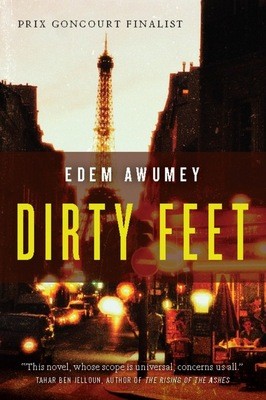

Dirty Feet

Edem Awumey

House of Anansi

$22.95

Paper

175pp

9780887842443

The short but dense novel recounts the story of an unlikely and undefined relationship between two migrants in Paris, both haunted by memories of their respective homes. The protagonist Askia suffers the somewhat typical fate of many immigrants: though he is well educated, he drives a cab and lives in squalor. He is also on a mission to find his lost father, who is believed to be living in Paris. One day, he meets the mysterious Olia (who happens to be his fare) – a Bulgarian fashion photographer who claims that she has photographed Askia’s father and offers to help locate the missing man.

“Dirty Feet” is the name given to Askia’s family, who were condemned to a nomadic life, unable to settle long enough to rest and clean their feet. As a symbol of mobility, feet serve as an apt synecdoche for the transient existence of Askia and other nomads portrayed in the book. Feet are often either, in one extreme, hidden out of shame, or, in another, fetishized. These two extremes serve as apt metaphors for both Askia and Olia’s experience of being foreign and transient. Olia represents the “exotic” immigrant qualities that society accepts, and even covets; her successful integration into Paris is signalled by her bright, spacious apartment and her lucrative profession as a fashion photographer. Askia, on the other hand, stands at the opposite side of foreignness, inciting fear and rejection. Hidden from others in his taxi, he provides mobility to the privileged Parisians who would rather not be associated with him outside of that context. His bare and shab- by room in the outskirts of Paris also symbolizes the downward spiral of a neglected existence that is neither cele- brated nor properly supported.

What seems to begin as a mystery and a potential love story takes a dark turn. Instead, the book explores the depths of Paris, unseen by most people. Askia’s Paris includes undocumented people running away from the authorities, regular harassment from skinheads invading his home and threatening his life, and probing customers who see his foreignness as either offensive or perversely desirable.

The tragedy of an abandoned son, reinforced by recurring allusions to Telemachus, son of Odysseus, runs parallel to the description of Paris’s dark underbelly. Like the labyrinth of a taxi driver’s daily route, the book travels back-and-forth between the past and the present. The nonlinear account is sometimes written as a straight-up expository, especially his encounter with customers; other times, the book borders on magic realism, as when Askia recalls an idealistic version of his father: “his turban, perpetually white, impervious to dirt… the rumour eventually spread that it was not the turban. It was his heart. His heart remained unsullied.”

Awumey adorns his book with short, vivid phrases that, at times, read like poems (“The Rom, his bloody head. A red ball. As on that maliciously sunny day when he had managed to beat the dog Pontos on the head with a chunk of hard mortar …”). Sometimes, the poetic tendencies yield clichéd phrases (“did you forget that it’s called the City of Lights? You can’t hide in the light…”) – but these instances are rare.

In Woody Allen’s latest film, Midnight in Paris, a white American man in a rut finds his inspiration and joie de vivre in the city. Unlike the easy romanticization of Paris in Allen’s film, Awumey’s text reveals the fictionality of such idealization by looking beyond the clean streets and brightly lit cafés. A finalist for France’s Prix Goncourt in 2009 (previously won by Marcel Proust and Romain Gary), Dirty Feet reveals the unsettling truth of an ugly racist reality even in a place celebrated for its culture and beauty. mRb

0 Comments