There is a moment in childhood that first marks our awareness of the wider world, the moment we recognize what takes place beyond our own sphere. Our young selves are drawn to the narrative, to the images played and replayed on the news, to the hushed thrall of the grown-ups.

In the spring of 1989, Madeleine Thien was fifteen years old. After six weeks of protests in Bejing, the public unrest culminated in the Tiananmen Square massacre. “It was,” the novelist recalls now, “the first time that I’d seen a world event unfolding in real time.”

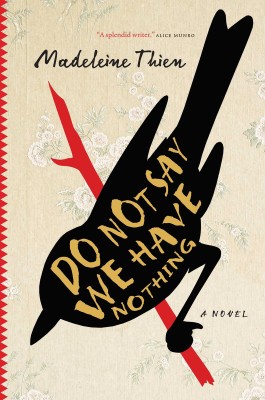

Her new book, Do Not Say We Have Nothing, she says, was seeded long ago: “I was drawn to Tiananmen Square because I remembered it so vividly.” Thien, who grew up in Vancouver, watched the imposition of martial law and the resulting civilian deaths at a cultural and generational remove. “These were my first images of what China looked like, what students looked like – people my age. I was a very idealistic young person, and I invested something emotionally in watching these images, thinking something dramatic was about to happen in China. And something did, but not what we would have hoped.”

Do Not Say We Have Nothing

Madeleine Thien

Knopf Canada

$35.00

cloth

480pp

9780345810427

When Marie is still a girl, Ai-ming, a young woman fleeing the post-Tiananmen Square repression, comes to stay with Marie and her mother in Vancouver. Marie’s father has recently died, and Marie is in dire need of a sister figure. As well as staunching her soli- tude, Ai-ming also provides the key to The Book of Records, an incomplete, hand-copied novel found among Marie’s father’s papers.

Part romance, part adventure, The Book of Records surfaces also half a century earlier, when a young dreamer named Wen uses it to woo his beloved. And, when Wen the Dreamer and Swirl, along with their daughter Zhuli, get swallowed by the violence of collectivization and re-education, the notebooks are recopied again and again with minute encoded alterations and scattered across the country to make the family whole again. Do Not Say We Have Nothing is Thien’s most complex work narratively. “I was trying to connect with an unfolding Chinese history since the Revolution,” Thien explains. “Because it’s still one moment, in a way.” There are more crackdowns today than ever. The Chinese, Thien notes, are even today forbidden from mourning the victims of the massacre, twenty-seven years on. Families are prevented from leaving their homes on the anniversary and on Qingming, the Chinese day of the dead. “The Chinese government has actually made it illegal to grieve. The right to publicly grieve the past, the right to grieve your children, your family, the right to grieve some of the tragedies of the Revolution, it’s simply not allowed.” Culturally, the imposed silence leads to a dispersal of clandestine thoughts, under an overwhelmingly utilitarian patina. As the novel’s matriarch, Big Mother Knife, muses, “Revolutionary music hurts the ears after a while. There’s no nostalgia in it, no place for people to share their sorrows.”

One of the recurrent sorrows in Do Not Say We Have Nothing is the piteous attempt to make amends, whether for transgressions real or perceived. As the state, its lackeys, and its ideological adherents stand gleefully as judge and executioner, the most heartbreaking atonements come by one’s own hand: “In this country, rage had no place to exist except deep inside, turned against oneself.”

To say Thien’s characters come to life is an approximation: they are at once so whole and so open that a reader can step into the book seamlessly, watching, shifting as the pages turn. The affinity reaches so deeply that we celebrate their hopes and mourn their losses; a death leaves me crying in my kitchen. Paradoxically, one of the consequences of forbidden mourning in Do Not Say We Have Nothing is hope: so constant is the characters’ struggle that we refuse to believe separation, or even death, is permanent.

As ever, Thien’s descriptions manage to have at once the lightness of the perfect, obvious observation, and the heft of time and place. Sunflower husks crack underfoot in a train car. As a wedding celebration gathers steam, Thien writes, “the party seemed to expand beyond its limits, twirling forward like a well-known song with extra verses.” The passage of “so many feet,” she writes, makes “a storm in the dust ….” My copy is dog-eared through with lines that ring and hold.

Thien writes terror well, too, distilling the enormity of the massacre into tiny terrifying chokes – the claustrophobia of the blockades, a colleague lost in the crowd, the stain of blood spreading over a young mother’s hair, her clothes, the child she carries. The passages that take place in the work camps are also chilling, in their banal exactitude – the busy deprivation, “nothing in our stomachs but an echo.”

But it is the music that most clearly marks this novel. Whether she is writing about Ravel, about silence or composition, the violin or the erhu, the fidelity is astounding – “a seam of notes that slowly widened,” as when Marie first hears Sparrow’s last composition for her father, his friend Kai.

Thien turned to music after writing her previous novel, Dogs at the Perimeter, which dealt with the whitewashed history of the Khmer Rouge regime in Cambodia. Writing the Cambodian novel was “devastating”: delving into that genocide, she came up against the lack of possible words to express the enormity of inflicted suffering. “That’s what I felt after writing that book: I had no words.” Listening to music provided consolation, “a gate to another way of experience, without words.”

What Mao did in thirty years – with as many as sixty million killed – Pol Pot did in three. Dogs at the Perimeter had a disconcerting proximity, an intimacy. There are more ghosts in the new novel, but there is also more space for them, Thien says, “the canvas is bigger.”

And it is timely. Tiananmen, the ongoing repression in China, even the Khmer Rouge – they are not yet history, Thien points out; they took place in our lifetimes. The act of writing is political for Thien, insofar as writers end up pointing out the cyclical nature of history. “This repetition keeps happening. And we keep essentially moving backwards.” In the novel, as the army holds the streets of Beijing, the students are upbeat: “Out of our sacrifice will be born a new China.” Does Thien foresee a resolution, nearly three decades later? “Not in China. Especially after writing this book. Not one that makes me feel optimistic.”

Though, as Swirl admonishes Wen in Do Not Say We Have Nothing, “it’s foolhardy to think a story ends.” The novel floats by like a dream of words, a piece of the story, in solidarity with its dreamers. mRb

0 Comments