Roughly a third of the way through Easily Fooled, the third instalment in H. Nigel Thomas’ planned quartet on the Caribbean Canadian immigrant experience, we meet Miss Collins of St. Vincent:

Her stick-like body was swallowed up in an ash-grey long-sleeve jersey several sizes too big and a dungaree skirt that reached down to her ankles, second-hand clothing her niece sent her from Toronto—God’s reward for her righteousness, Miss Collins often said, pointing out the package to all she met on her way from the post office, and she backed it up with a quote from Deuteronomy.

It’s a sentence that deserves rereading. There’s a story in every detail, and its layered portrait is all the more notable for being lavished on a character who is, at best, a passing figure in the novel. If it wasn’t already clear, Miss Collins makes it so: Thomas is a writer who doesn’t miss anything.

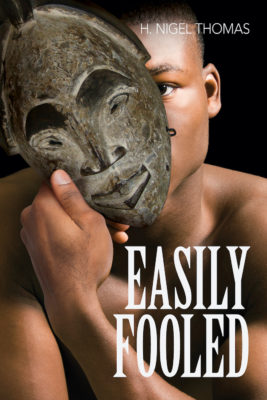

Easily Fooled

H. Nigel Thomas

Guernica Editions

$25.00

paper

330pp

9781771835817

In Montreal, Millington hangs with a metrosexual bunch known collectively as Les Friends, but finds it hard keeping up with their libertine ethos. Instead he’s in an extension of the struggle he faced as a conflicted minister, a battle “between his authentic self and his public self.” In the words of his husband, he needs to “clear [his] brain of all that theological debris,” but it’s easier said than done. “When he became agnostic,” says Millington’s once-removed narrative voice, “the space belief once filled became excruciatingly empty. It’s still empty.”

Millington is trying to reconcile a family legacy that was itself lived out in the shadow of colonialism. Looming large is his father, Edward, of whom the best thing that could be said is that, unlike most Vincentian men of his generation on, he didn’t beat his wife. In a milieu where the men “flaunt children as proof of their virility and see the children’s needs as their mothers’ responsibility,” Edward squandered the household’s stretched budget on drinking and womanizing. Learning much of this on his father’s death, Millington “felt that if he’d known that Edward valued maintaining a mistress – and for short periods mistresses – over funding his education, he might have come to despise him.”

The novel’s St. Vincent flashbacks are filled with the kind of images that one feels had to have been lived, like this one: “Some afternoons, especially during the rainy season, when landslides often delayed the bus, Millington was too tired to do homework.” It’s in these parts of the book especially that readers might be reminded of V.S. Naipaul, and there’s more to it than the Caribbean connection. Like the early Naipaul of A House for Mr. Biswas, when there was still a generosity of spirit to the future Nobel Laureate’s work, Thomas possesses the rare ability to telescope a whole culture into an intimately scaled frame, deploying a dispassionate eye, pin-sharp dialogue, and deft touches of humour.

As the setting shifts between St. Vincent and Canada the contrasts can be jarring, but that’s probably the point: Millington is negotiating the aftermath of a profound rupture, and Thomas’ great achievement is to give a vivid sense of that rupture – its costs and, occasionally, its consolations. mRb

Editors’ note: an earlier version incorrectly named the main character’s husband, Jay, as Pat. This mistake appears in our print edition. We regret the error.

There is no Pat…. in this particular novel.

Fixed, thank you!

I’ve met Nigel – he’s a lovely man and his work is profound. Thanks for such a lovely review.