My first encounter with Oana Avasilichioaei’s sixth poetry collection, Eight Track, was in performance. Combining live sound creation with both pre-recorded and computer-generated voice and a compelling video projection (in collaboration with Jessie Altura), “Operator” offers an immersive, lightly performative audiovisual iteration of what is now also presented as two separate poems in the print book (namely “The Drone Operator” and “Drone Operators”). When I ask Avasilichioaei whether the performance piece or the print versions of this work came first, she explains that the creation of different renditions of the same work often happens simultaneously, and these versions mutually impact one another so that it is ultimately irrelevant which one originated the process.

She clarifies:

The print, visual, performative, and sonic versions of a poem influence and inform each other, sometimes quite significantly. Fundamental differences, but also resonances, exist between live, inscribed, visual, and digital contexts. Sometimes I’m interested in translating the experience of one context to another. Other times, I want to highlight their dissonances.

The affordances of performance versus print versus the digital archive and more may all be different, but these divergent modes for disseminating resonant poetic thoughts harmonize across media formats. One of the many strengths of Avasilichioaei’s practice is that a reader can pick up the material object that is the book and flip through its pages, then transform into a listener attending the public, sensory expansion of the book’s words into sound, while simultaneously morphing into a viewer of art, a critical thinker, and even a participant implicitly invited to adapt one of the poems as a script for further improvisation and production. The multiple embodiments of similar poetic material coexist, both pushing back and supporting one another to create a choral structure of creative output that oscillates in form but also merges and overlaps in content.

This choral simultaneity of works is further reflected in the book object that is Eight Track itself. For one, it is populated with voices that speak solo, harmoniously in groups, or as a contradictory cacophony. The opening poem, “Voices (remix) Side A,” for example, revolves around subject positions called “one VOICE,” “a VOICE,” and “VOICES.” Each and all of these voices expand and contract from silence to restlessness to symphonic crescendos, tantrums, and noise. “To deny existence is to deny a VOICE,” writes Avasilichioaei, applying a metaphor of voice as self- expression and personhood, and articulating a dominant theme that runs throughout the book.

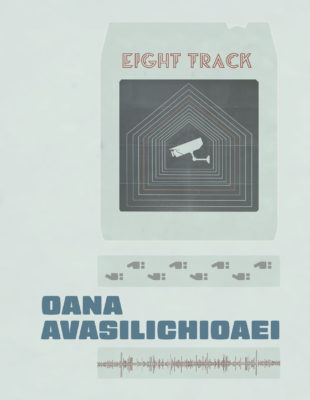

Eight Track

Oana Avasilichioaei

Talonbooks

$19.95

paper

208pp

9781772012385

“A voice is always multiple,” Avasilichioaei tells me, “I purposefully work against trying to singularize it – the individual as (discordant) chorus.” Her words remind me of a neologism from the book’s final poem, “Tracking Animal” – “singpluranimal” – the animal, the entity, the being, is both singular and pluzral, and while the word “plural” is extended into “animal,” “singular” is abbreviated into song. Constantly moving between subjectivity as both individualized and multitudinous, the animal, the entity, makes itself heard, sings, and voices itself. A voice can function in different ways, and it can sound itself in parallel to other voices or against the grain.

The voice of Eight Track as a whole fuses together as a formal and thematic unity while also retaining independent poetic strategies in the eight main sections of the book (and a hidden bonus track!). Each section is framed by a definition of the word “track,” ranging from a musical track to surveillance tracking to a beaten track across a landscape, and more. Some of these tracks strike a discordant note.

“A Study in Portraiture,” for example, homes in on surveillance technology in Montreal’s Plateau neighbourhood and includes a series of photographs of security cameras found in close proximity to the poet’s home. As Avasilichioaei explains, photographing these cameras that are likewise photographing her is an attempt to reverse the panoptic gaze, to create a moment of reciprocation in an otherwise onesided interaction of suspicion and malaise. I would further suggest that by stopping in front of the almost seventy cameras in her close vicinity and making eye contact by way of a snapshot through her camera lens, Avasilichioaei leaves traces of herself in her home environment; she lays a track of herself being tracked as one strategy to take back agency, to take back the resonance of her steps along the city sidewalks.

Reversing the eeriness of urban surveillance, the book’s second set of breathtaking, full-colour aerial photographs, “Trackscapes,” features the ancient Nasca Lines in Peru. In a thoughtful endnote on her positionality in relation to these cultural sites, Avasilichioaei writes, “so many meanings of track or tracking are negative, oppressive. The Líneas de Nasca stand in stark contrast to offer positive traces of human endeavour and survival.” Lines and grooves recording a civilization, the Nasca Lines reach out anachronistically to the title word itself – the eight track as an outmoded magnetic-tape audio recording technology is made up of four sets of stereo tracks allowing for independent audio strands to be present on the same tape. Eight track and Eight Track are therefore lines of sound melding as a technological chorus with individualized voices reaching out from the past into the present and future.

All this talk of voices – “the deafening murmur of a thousand voices” as Avasilichioaei poeticizes – also places her newest publication in dialogue with preceding books, performances, and projects. As these various forms of creative output mutate and progress, they also retain preoccupations with language formation and multilingualism, poetry as a process of thinking and philosophy, political engagement, and ethical awareness. These themes trace a lineage from Eight Track back to earlier works, such as my personal favourite Limbinal, through the A. M. Klein Award-winning We, Beasts, to Expeditions of a Chimæra, written collaboratively with Erín Moure. Avasilichioaei’s prolific translation work – and notably her acceptance of the 2017 Governor General’s Literary Award for Translation (for Bertrand Laverdure’s novel Readopolis) – further highlights her ability to voice herself with, in, alongside, and through the voice/s of others. She consistently expresses herself with incisiveness, is able to control her voice as an interpretative instrument in performance, and plays with the potential of language both in terms of meaning and affect.

“One of poetry’s strengths,” Avasilichioaei assures me, “is that it can encourage critical thinking by offering multiple, concurrent, and sometimes conflicting readings.”

Reflecting on the current, collective climate of COVID-19, she continues, “Now more than ever we need to seek out multiple narratives, sources, perspectives, possible actions, to remain elastic and restless in our thinking, and poetry can be a great catalyst for this.” As a generous member of Montreal’s literary community, Avasilichioaei underscores a wider claim about the resilient and vibrant potential of poetry; not only does poetry fuel, nurture, and connect us during this time of social isolation, but it also activates our minds and voices, amplifies the creative dissonances and harmonies inherent to reading, writing, listening, and speaking. mRb

0 Comments