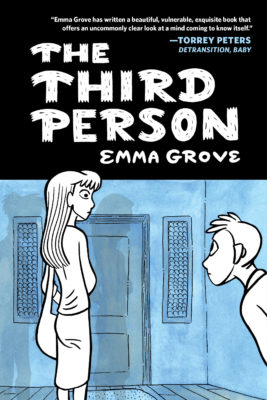

The title of Emma Grove’s remarkable graphic memoir is an ingenious bit of multi-layered wordplay. The practice of referring to oneself in the third person, when employed by the disproportionately famous, is an ego-driven self-indulgence. But for those of a more humble persuasion, it’s more likely to be a coping mechanism – a distancing device rooted in the sincere belief that the self being presented to the world is not the true self. Meet… well, meet Emma Grove.

The Third Person Drawn & Quarterly

Emma Grove

$49.95

paper

920pp

9781770466159

In what she hopes will be a practical step toward obtaining a referral for the hormone treatments she will need, Emma begins to see a therapist, Toby, who is also trans. A significant percentage of the book’s epic length focuses squarely on these two, sitting face to face in a sparsely furnished room. It’s complicated, though: in another spin on the title, there’s sometimes another presence in the room, perched behind Emma’s shoulder like a spirit animal. Emma and the reader can see this figure, but Toby can’t, and he is often left guessing as to which of three possible personae – yes, three – he might be facing at a given moment.

Emma, it has to be said, is not always easy company. Readers may sympathize with Toby’s occasional exasperation because, immersed in Grove’s patient, deliberate storytelling, they’ll be experiencing the same exasperation themselves, in what feels uncannily like real time. But as it dawns that Toby might not be the ally he first appears to be – he’s impulsive, slippery, and ethically sloppy, putting up seemingly unnecessary roadblocks at every turn – Emma’s fight grows even more daunting.

The comics medium is a perfect choice of form to deliver the story Grove is telling. Her drawing style might at first look naïve, but nuances emerge: she proves uncommonly adept at depicting the slight physical changes – in facial expression, in posture, in countless body-language tics – that can give a person’s emotional state away no matter how much they might want to conceal it. Formally, too, she incorporates enough variety to keep things fresh. At certain crucial junctures, a solid black panel is deployed; while its purpose shouldn’t be revealed here, suffice to say it’s a dramatic and efficient shorthand for a central aspect of Emma’s challenge.

Shall we address the elephant? Yes, let’s. The Third Person is indeed 920 pages long. But any notion that it might require an unreasonably demanding time investment should be banished. In an informal survey, this reviewer found that readers are likely to finish it in two sittings at the most. The primal, built-in narrative impetus is aided by Grove’s economy with text. Every word here counts. (It’s best to resist any temptation to flip ahead to the endnotes Grove provides. Their elucidation is ideally accessed the honest way, after a full read.)

Episodes from Emma’s childhood and adolescence are portioned out sparingly, but in judicious quantity and at ideal intervals: we get an organic sense of what has brought her to the impasse where we first find her. The heart of the book, though, is her adult battle to become who she is. While the very existence of The Third Person is proof that that battle was ultimately won, Emma Grove has created a stunning artistic testament to the spirit and strength of will it required.mRb

0 Comments