Balarama Holness has a good story to tell, and he’s a great storyteller too.

Eyes on the Horizon, the ex-CFL player, politician, and social justice advocate’s memoir, is an effortlessly engaging read. It comes across as particularly earnest and sincere, contrasting sharply with the book of another recent mayoral aspirant – Denis Coderre – whose 2021 personal memoir/municipal election platform, Retrouver Montréal (Rediscovering Montreal), fell flat with critics as much as the reading and voting public.

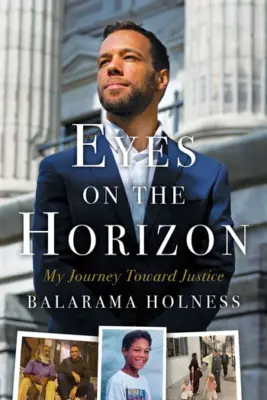

Eyes on the Horizon

Balarama Holness

HarperCollins Publishers

$23.99

paper

224pp

9780063111950

Irrespective of any political intent behind the book, it’s worth reading if for no other reason than to gain insight into the perspectives of a representative of the growing community of Quebecers who have been, and (unfortunately) will likely continue to be, treated as suspect outsiders by the province’s political and media establishments. The fact that Holness is still a young man brings the immediacy of the racism he experienced growing up into sharp focus. For those who would claim such problems only exist in the past, or far from the polyglot and cosmopolitan metropolis of Montreal, as an elder Millennial, Holness reveals that the problems he encountered are not only recent memories, but that they occurred right here in our city (or its immediate suburbs) as well.

Despite the presumed advantages of having parents from both of the city’s major linguistic camps, or of being a biracial, multicultural person in a city that ostensibly values diversity, Holness’ memoir demonstrates such is not the case. As important and inspiring as it is to read about how someone overcomes adversity to succeed beyond expectation, the lingering problem – as made evident in Holness’ account – is how much of that adversity is rooted in the profoundly racist society we live in, as much a Quebec problem as it is one inherent to Montreal.

Despite what we might presume to be the advantages of his birth, Holness confides how he was always an outsider rather than someone on the inside track. It gives the reader good reason to pause and take stock of the myths we tell ourselves about what Montreal is. Holness is a genuine outsider – as he describes it, not Black enough, not white enough, not French enough (or, in a manner of speaking that only Montrealers might understand, “too English”) – yet seemingly constantly told he’s a poster boy for the post-racial, inclusive, and diversity-positive city its political class allegedly aspires to. Holness is representative of a curious demographic phenomenon: the growing percentage of the population that doesn’t fit neatly into either of the traditional ethnolinguistic camps, whose experience of multiculturalism in Quebec is (unfortunately) also one of marginalization and near-constant othering.

And yet, this is unquestionably a book not only about one prominent Montrealer, but a book about Montrealers and the city they live in. It is instantly recognizable, though Eyes on the Horizon is written as though the intended audience had never visited the city before. It is a peculiarly consistent characteristic of the memoir, and perhaps my only negative criticism: for a book that otherwise seems to so clearly know its audience, the descriptions of the city almost seem intended for a visitor from abroad. Perhaps this is indicative of Holness’ higher aspirations.

There are some minor inconsistencies in the narrative, such as Holness providing ample examples of his mother’s unreliability, and then calling her the most reliable person in his life. There’s also an annoying tendency for people to pop into the text without context or introduction of who they are.

All of these are minor quibbles that in no way take away from the trenchant social critique of contemporary Quebec society, the insight into the “allophone” worldview, and a particularly incisive criticism of Mayor Valérie Plante and Projet Montréal’s use of people of colour as props for the campaign trail, whose concerns and “ties to the community” were abandoned and forgotten almost immediately upon Plante’s ascension to office.

After reading Eyes on the Horizon, I’m confident we’ll be hearing from Holness again soon, either in political campaign mode or agitating for an important social justice cause he believes in. However, I’m almost more interested in what he might reveal to us if he used his interpersonal skills and strengths as a storyteller to interview Montrealers of colour and those outside the traditional linguistic and cultural divide, to find out what the city and its culture and society look like to those on the outside looking in. I believe that such a project would affirm Holness’ revelations, and if so, we might brace ourselves for a considerable shock. Les apparences sont souvent trompeuses.mRb

It is a powerful and inspiring book that will stay with you long after you finish reading it.