In Marc Ménard’s Firebrands, Philippe Bordeleau’s settled, humdrum professional and family life in Montreal is about to be thrown into “disorder and chaos” by his old friend, Robert Moranowitz, known as Mora. This is clear to him when he sees Mora outside his front door on an October morning of 2002.

The two have a history going all the way back to Philippe’s student days in Paris, in the late 1980s. Some unfinished business has prompted Mora’s sudden appearance on this side of the Atlantic, fifteen years later, in front of Philippe’s home: notorious far-right underground leader Hans Wolf is out of prison and back at it. Mora has one last plan to prevent Wolf from putting his democracy-destroying stratagem into action, and he needs Philippe’s assistance. Mora’s charisma, still very much there in spite of his failing health, is too great to ignore. Regardless of all the danger involved, and against his better judgment (and that of his wife, Madeleine), Philippe has to help his old friend one last time.

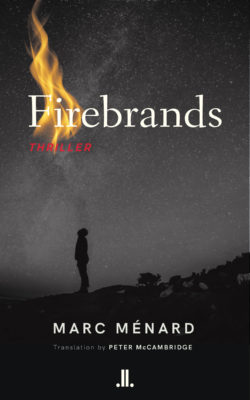

Firebrands Linda Leith Publications

Marc Ménard

Translated by Peter McCambridge

$24.95

paper

200 pp

9781773901053

The chapters alternate between Philippe’s life in the fall of 1986 in Paris, where he met Mora and was introduced to the life of a spy, and his life over the course of the month of October 2002, when he follows, almost blindly, the plan Mora has concocted to stop Wolf. In the Paris chapters, we learn that both men are linked to Madeleine, another Montrealer living in Paris at the time. In all of her interactions with the two men, past and present, she comes through as the voice of reason, though her advice falls by the wayside early on in the novel.

The narrative’s plausibility has its weak points. Is Philippe really that gullible? Is Mora really that good of a manipulator? The story could have been fleshed out some more. The guru dynamic Mora inspired in his “followers” and Philippe’s decreasing adherence to this cult-like way of life gave me the impression the story was going elsewhere on one or two occasions. Could Mora also be a person who needs to be stopped?

The questions the novel seeks to raise, although perhaps naïvely introduced, come through loud and clear. How far are we willing to go to stop threats posed by the far right? What kind of violence are we ready to inflict in so doing? Is violence an answer to violence in the first place? (On the topic of violence, I must include a trigger warning here. The novel does contain one shockingly disturbing scene.) And to return to Madeleine’s narrative presence, what about our willingness to take our heads out of the sand in the first place and do something about it?

In the end, these questions transpire so strongly from the story that I am left to wonder if they weren’t what actually motivated Ménard to write the novel in the first place.mRb

0 Comments