Joe Ollmann isn’t comfortable with praise. On the back cover of his new book, the graphic novelist professes to blush as he hand-letters glowing testimonials from fellow cartoonist Seth and culture journalist Jeet Heer. But if the collection Happy Stories About Well-Adjusted People is anything to go by, he’d better get used to such things.

Ollmann cites Peanuts, Spiderman, Captain America, and Mad magazine as early formative influences, but perhaps a better indication of his sensibility would be the American realist tradition epitomized by Harvey Pekar (American Splendor) and Robert Crumb in his more restrained mode. He’s got kindred spirits in literature and music, too – like Charles Bukowski and Tom Waits, he expresses compassion for society’s downtrodden and marginalized through vivid narratives that get right in the muck and murk of life. And like all of the above, he can shift from wrenching to gut-bustingly funny in a blink.

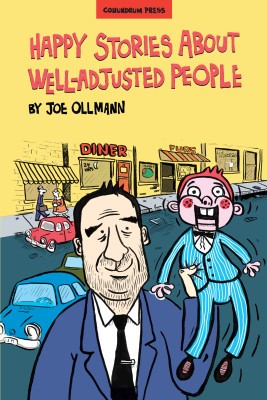

Happy Stories About Well-Adjusted People

Joe Ollmann

Conundrum Press

$20.00

cloth

244pp

978-1-894994-86-6

Joe Ollmann: I’m definitely more of a writer who also draws. I mean, I work hard on the visuals, but I am always acutely aware of my limitations. And it helps that every review of my books always mentions my “grotesque, claustrophobic, ugly” artwork. I’m like, “I know, I know.” I guess I’ve grown accustomed to my art and am resigned to it, trying to improve the elements that I can, cognizant always that I ain’t never gonna be no Rembrandt.

The stories definitely come first. I generally write a straight short story and adapt that into a comic script where some interior monologues and descriptions will become narration, then I storyboard that and break it down into pages. I know some cartoonists who work unscripted, or from a rough outline, but I go in from the beginning like a general planning a massive attack.

IM: To what degree do you feel your characters need to be conventionally sympathetic? Do you enjoy walking that likeable/unlikeable line? It could be that I’m thinking of the protagonist of “Hanging Over” here.

JO: Probably subconsciously my ex-Catholic need to be good stops me from writing completely unsympathetic characters. You spend a lot of time with the characters you write, so you tend to make them likable to yourself to some degree, like the people you choose to surround yourself with in real life. I also think that completely unsympathetic characters, while they may be interesting as biological specimens, are pretty hard to relate to or root for, and I always want people to care about the people I write about like I care about them.

IM: The heroines of “Big Boned” and “Otherwise, Arachis Hypogaea” are two of my favourite characters in the book, and show a real ability on your part to empathize with female characters. Insofar as it’s possible, could you tell me about the genesis and development of one of them?

JO: Charlene in “Big Boned” came from a small incident on a bus a long time ago. This drunk old guy was annoying this young woman, hopelessly flirting with her and annoying the hell out of her, but she was politely and shyly kind of tolerating it. I could see that the old man felt he could get away with it only because she was overweight and therefore “flawed” and would possibly lack the confidence to tell him to f—k off. And watching her, I was like, “Why is she being polite to this piece of shit?” I was feeling all noble and kind of physically insinuated myself in between them and did my smile that says “Aren’t I a good person?” that I usually reserve for gay couples holding hands or disfigured children, to let them know I’m a good person who likes them. So I guess I was probably filled with such self-loathing at that moment that I projected it onto her and thought of how annoyed and angry and full of rage she must be, not just against the drunk but against me, the smug self-righteous guy making assumptions about her.

I grew up in a house with four sisters and I got married young the first time – 17! – and I had two daughters at a very young age, so I’ve had a lot of female influence all my life. I would hope that that would allow me to write female characters well.

IM: Should readers be looking for auto- biographical clues in your work? How present are you in your stories?

JO: People have written to me, concerned about me, after reading “Hanging Over.” They thought it must have been based on something real, like I was an alcoholic and had a mentally handicapped brother I didn’t want to take responsibility for. But no, though there was a time [when] I could relate to the problematic drinking and I could write that stuff from hard-earned experience. Those days are over; I’ve been off booze for over a year now. I’m like an ascetic monk, though less humble about it. I flatter myself that it’s my fantastic, empathetic authorship that causes this autobiographical confusion, though an easier answer might be that I tend to draw my main characters to sort of resemble me.

IM: “Pathetic majesty … maudlin, shaggy clown …”; your self-portrait in the afterword almost seems designed to pre-empt anticipated criticism. How much attention do you pay to reviews and to response from readers and peers in general?

JO: Oh shit, I pay too much attention to reviews and random blogs and what my peers think and what strangers say on Goodreads. All this constant feedback that’s available is such a stupid distraction. I really am striving to not give a shit about it anymore.

Not bragging, but I almost always get good responses from reviewers. CBC just said I am to graphic novels what Alice Munro is to fiction! Ridiculous hyperbole, but I’ll take it. Of course, the things that resonate and stay with a self-loathing author are not the kind words from erudite, respected institutions, but “You suck!” spelled incorrectly on someone’s blog. That’s the stuff I fall asleep thinking about.

IM: A lot of people still have a somewhat limited view of what “comics” are and can be. Do you find, as a practitioner of the form, that it entails a certain implicit pressure to be funny, or do you find that the form allows for all the emotional and tonal scope you need?

JO: Art Spiegelman did all serious cartoonists a favour forever with Maus. It’s always trooped out – “Jesus, this guy made a comic about the friggin’ Holocaust and it works!” It really made it easier for everyone else that that was a bestseller and won the Pulitzer.

I don’t feel a pressure to be funny; I just can’t help it. I think it’s also a sign of maturity. Being all dark, serious, and earnest is a young person’s game. As you grow older and you get closer to the grave and you suffer life’s constant stream of humbling, hilarious situations, I don’t know how you could write anything without injecting humour. mRb

0 Comments