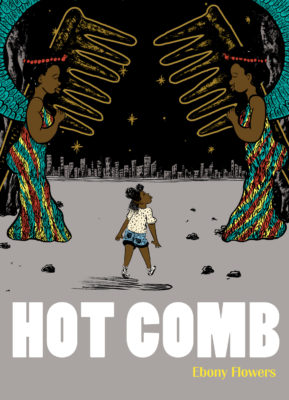

In her lively debut collection of short comics, Ebony Flowers illustrates the lives of Black women and girls, using hair as a way to explore self-image, intimacy, family bonds, friendship, racism, and colonization. Hot Comb’s titular story is a coming-of-age tale, in which a young girl begs her mother for a perm and endures the chemical pain of it, only to be teased mercilessly the next day by the peers she wanted to impress.

Black hair, its care and its codes, is central to each narrative, as is the social space that opens up around it. Often, Flowers portrays her characters getting their hair done at salons or by friends or relatives. Conversation starts to flow as one woman combs another’s hair, parts and clips it, twists it. Worries, memories, and hopes start to spill out. In “Sisters & Daughters,” Latreece takes her daughter to the park, where her sister meets up with her to do her hair. As the sisters’ hair date gets underway, Latreece laments her girl’s childishness. At first, it’s hard to sympathize – her daughter is very young, and Latreece’s attitude seems overly harsh. But as her sister does her hair and they keep talking, family history emerges, and we begin to understand Latreece’s own childhood and the ways in which early responsibility has made her brittle. We also see her sister working to soften her, as she works her hair into a new shape. “Hold your head down,” she directs, as Latreece brings up old family hurts, and “Let that girl be a kid for a while.” There is no emotional epiphany at the end of this vignette, just a small shift, a slight relaxation brought on by sisterly care in the space of a hair date.

Hot Comb Drawn & Quarterly

Ebony Flowers

$24.95

paper

184pp

9781770463486

The drawings that accompany the title pages of each story also form their own wordless arc. The narrative that emerges counteracts some of the stress and pain undergone by the women and girls of Hot Comb. A child stands outside in a gathering rainstorm: at first, she looks worried that the rain will ruin her hair, but slowly, she smiles and relaxes. Eventually she begins to dance in the downpour, and finally, she stands there dripping, hair frizzy – the storm has passed and her hair got soaked, and she’s grinning from ear to ear. mRb

0 Comments