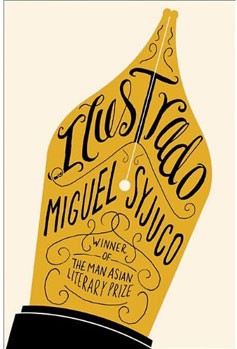

Ilustrado

Miguel Syjuco

Penguin Canada

$34.00

hardcover

256pp

978067063956

On becoming a writer

“I’ve always been a reader, but never thought I had the chops to make it as a writer. I took up economics in college (in the Philippines) because I was going to go into the family business, which was soft-drink bottling. I failed because of math and had to get a new major. I thought, ‘I’m in college, I want to chase skirts and drink beer,’ so I took the path of least resistance. I took up English lit. I started writing poems and short stories. They weren’t any good, in fact they weren’t even good enough to let me write a thesis, but I found that I enjoyed

the challenge, the very elusive and all-too-brief feeling of finding a rhythm while writing, finding this joy, this white heat. That’s addictive. It’s like gambling or drugs. The high is just enough to keep you coming back, even though the comedown hurts.”

On literary influences

“The first thing I ever wrote was the sequel to The Lord of the Rings, in Grade 5. Thankfully that’s lost to history, but Tolkien got me into reading and writing. Later heroes were C.S. Lewis, Isaac Asimov, Saul Bellow, Nabokov, Borges, and very recently Bolaño. I always return to Hemingway, the rigour of the writing. He brings it back to the level of the sentence, and that is so important. A personal writing epiphany? Finishing Ilustrado taught me a lot. It’s such a big beast, a novel. It really is like climbing a mountain, so when you get to the summit, you realize that you can do it. It will never be as good as you want it to be, but to finish it gives you confidence – or fatalism, despair that you’ve invested so much that you might as well just see this damn thing through.”

On unlocking the key to Ilustrado

“There were so many fragments that I couldn’t really envision it in terms of chapters and the whole. Then one day I was watching a documentary about weavers in the Philippines. I watched as these women first created each individual thread and then fed them into a loom to create patterns. I thought, ‘That’s fantastic. This is how I need to write my book.’ So I raced to the computer, I opened up ten Microsoft Word documents, and I took my manuscript apart, developed all the single threads just as I’d seen those old women do, then wove them together. I devised a system whereby I summarized each of the fragments in one line, colour-coded them according to which narrative thread they belonged to, printed them out on card-stock paper and backed those with Velcro. Velcro plays a crucial part in all the good things in life.”

On the writer as spokesperson

“I worked on this book for four years. It was a very long trajectory. In the beginning I thought, ‘Yes, okay, I am going to be representative (of the Philippines).’ Having finished the work, having grown up a bit and become less prone to hubris, I’ve realized how unfair it is to put that on an author or a book. If I do try to do that, I’ll only always fail – it becomes more polemical, more grandiose. Now I think my role isn’t to represent, it’s to write as honestly and as authentically to my own little slice of the Filipino experience as I can. If I’m authentic

to that then I’ll always be authentically Filipino.”

On Ilustrado’s reception in the Philippines

“The book was first launched there, and I went home with some trepidation because it is a satirical book, it is brutally honest. It does try to raise more questions than it attempts answers. But for the most part it’s been accepted very well. Readers, especially, have taken to it. I can see on blogs that people are quoting the book. I get the impression that for many people it’s articulating some of the frustrations we all have. What more could a writer ask? But then there are other writers at home who are less enthusiastic with it. This book, by a Filipino, about the Philippines, received no help whatsoever from any other Filipino writer. No one wanted to help me.”

On the low world profile of Filipino lit

“We’ve been writing in English for a hundred years. You’d think that we’d have more out there. I think we’ve suffered from, first, trying to mimic the way American writers write, because we were a colony. Then we fell prey to fads – magical realism, then the whole Asian-American, Amy Tan thing, that identity boom. I think readers sensed that we were facsimiles. And we exoticized ourselves. So many books had the requisite water buffalo in the rice paddy, sunlight the colour of mango, earth the colour of tamarind, all that crap. Exotic fruit being celebrated as sensuality. I set out to write against that and I think others are now too.”

On CanLit and his place in it

“The more I read Canadian literature, the more I realize that it’s multi-faceted, a lot less homogenized than in other countries. I’m feeling like, ‘Yeah, I can be a part of this.’ I like Joseph Boyden a lot, the way he takes his background and turns it into something meaningful and universal. M.G. Vassanji too. Michael Ondaatje perfectly represents what Canadian literature is and can be. He comes from somewhere else, writes about somewhere else, but is nothing if not Canadian.”

On dealing with reviews

“It’s a contradiction, because to write you need to have very thin skin, you need to be sensitive, but to publish and promote and read your reviews and move forward you need to have very thick skin. I’m having a really hard time with that. By and large the reviews have been good, and even in the bad ones the things pointed out as weaknesses I’ve often agreed with. I don’t want to ignore (negative reviews) because I want to grow as a writer, and it’s a conversation. Good reviews are dangerous because they can go to your head.” mRb

0 Comments