Larry Tremblay’s Impurity is a literary mystery. Antoine, a middle-aged Montreal professor, grieves over the recent death of his wife, Alice, a bestselling novelist, as well as the suicide of his long-lost friend, Félix. An intellectual grump who’s always dismissed sentimentality, he struggles with the waves of emotion that wash over him as he tries to process this double loss. Between this struggle, a series of flashbacks to the trio’s youth in Chicoutimi, and a subplot about Antoine’s alienation from his adult son, Jonathan, the novel touches on deeper and darker themes as it progresses.

Antoine is the type who lives fully in the highbrow world of philosophy and literature, and is overt in his contempt for religion, pop culture, displays of emotion in general, and anyone with an opinion different from his own. He’s unabashedly pretentious, arrogant, and confrontational to the point of cruelty – the kind of personality that’s slightly charming in a young student, much less so in a middle-aged man – and appropriately, the scenes during the characters’ youth are full of energy, just as the later ones drip with bitterness. Tremblay smartly plays with our sympathies: Antoine is quite unlikeable, but you can’t help but feel for him as he confronts the surges of feeling he’s always disdained in others.

Impurity is a literary hall of mirrors. There’s a novel within the novel, and then another one inside that one. Although at first glance that might seem like a tired exercise in postmodernist gymnastics, Tremblay nails the tricky task of making it emotionally resonant. In fact, the self-reflexive meta-move doesn’t even come off as clever, but rather is an integral part of the mystery that Tremblay slowly unfolds over the story.

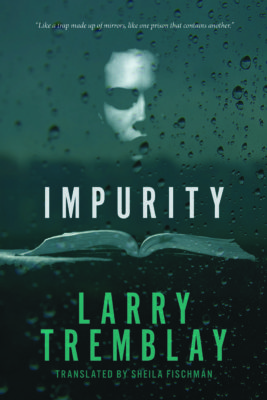

Impurity

Larry Tremblay

Translated by Sheila Fischman

Talonbooks

$19.95

paper

180pp

9781772012477

Tremblay’s own literary style, as rendered by master Quebec translator Sheila Fischman, is straightforward, almost stark, an effective contrast to the emotionally heavy material. My only criticism of the translation – and I’m fully willing to admit that it may be petty – is the repeated use of the verb “zap” for TV channel surfing. I’m pretty sure this is not an expression that any Anglophone has ever used, at least outside of Quebec. Then again, maybe a French anglicism, transposed to Québécois English, is appropriate for the multilayered reality of this novel.

I would have liked to read a bit more about Félix, the old friend who’s as emotional and spiritual as Antoine is coldly rational. Félix’s deeply held beliefs are tied up in the loss of his beloved cousin, who was never found after the (real-life) 1971 landslide in the small Quebec town of Saint- Jean-Vianney. We never get to know him as well as the other characters, but perhaps that was necessary to keep the narrative as tight as it is.

Impurity isn’t fun, per se – it’s too dark for that. But it’s a page-turner all the same. Despite the darkness, the meta-structure, and the setting in the insular world of literature, it’s as suspenseful and readable from start to finish as an airport mystery paperback – a nifty literary trick that Tremblay pulls off with aplomb. mRb

0 Comments