Since the armistice between Allied forces and Germany was signed on November 11, 1918, we have certainly not lacked in books or movies about World War I and the violence that rippled through Europe. With her latest work, author Dianne Graves attempts to showcase a side of the war that many Canadians may never have heard of before: that of the women who stood in the background of battle.

In the Company of Sisters: Canada’s Women in the War Zone, 1914–1919 explores the personal experiences of Canadian women who made the long voyage overseas to help as best they could at the time. Graves explains that women mainly wished to join the war effort for two reasons: firstly, for the British Empire (Canada was only about 50 years old at the time, and loyalty to Britain was still quite a thing) and secondly, for a nascent desire to be independent.

“Those in a position to pursue a professional qualification in fields such as teaching or nursing found it was increasingly regarded as an important step towards the kind of independence that a growing number of young women were seeking,” explains Graves. Women joining the workforce during the war coincided with women’s push for basic rights in Canada, a movement mostly fuelled by women from the upper classes. As such, the women who went to war were for the most part liberal-minded and wealthy, especially since the cost of sailing to Europe was so high.

The majority of the Canadian women worked as nurses (or, as they were referred to at the time, “sisters”), and Graves argues that what distinguished Canadian nurses from their colleagues abroad was the high quality of the training they had received in Canada. The first half of the book delves deep in the inner workings of wartime nursing as Graves describes in detail the establishment of hospitals and the services offered in different locations: England, France, Greece, the Balkans, the Middle East, Russia, and at sea.

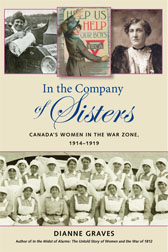

In the Company of Sisters

Canada’s Women in the War Zone, 1914–1919

Diane Graves

Robin Brass Studio

$27.95

paper

384pp

9781896941769

However, the perspective of the profiled nurses does not give more historical context of the areas in which they are stationed. For example, four Canadian nurses find themselves in Petrograd during the Russian Revolution, even meeting the czarina and her daughters, but the last Empress of Russia is simply described as “very gracious” and the Revolution as “so well managed.”

Nursing wasn’t always the only option for Canadian women wanting to lend a hand. Many, also from privileged backgrounds, travelled to Britain as volunteers. Margaret Watt from British Columbia helped set up the British Women’s Institute to train women in agriculture, while Toronto’s Mary Gooderham ran an organization called the Imperial Order Daughters of the Empire – which might sound straight out of Star Wars, but was an organization uniting “women and children of the British Empire” to raise funds for essentials like a hospital ship and ambulances. Many wealthier relatives of Canadian soldiers were also able to travel to be closer to their loved ones and aid with relief work. Journalism was another way for Canadians to play a part during WWI, by bringing stories of the war back home. These stories were told by many women war reporters, including Elizabeth Montizambert for the Montreal Gazette.

Graves dedicates each of the last four chapters to specific women: Lady Grace Julia Drummond for running the Information Bureau of the Canadian Red Cross Society, Lena Ashwell for helping to organize and perform in Concerts at the Front, Julia Grace Wales for her peace activism, and Mary Riter Hamilton for depicting the aftermath of the war in her paintings. These chapters balance the book with stories of what happened beyond the hospitals and medical services. I would have liked more than one chapter on the women pushing for pacifism at the time. In the section about Ashwell and entertainment for the troops, there is a mere sentence about the popularity of drag artists during WWI, which I think would also be interesting to explore in greater detail.

Meticulously researched, Graves’ work will be of interest to Canadian history buffs seeking to learn more about the role we played during WWI and how its tragedies affected us. But others, especially younger generations of Canadians, might find it harder to relate to the level of patriotism (each chapter starts with fragments of poetry written about the war), the distinctly privileged perspective, and the loyalty to the British Empire documented here. Graves obviously cares deeply for her subjects, but In the Company of Sisters sometimes reads more as a homage to these women than an unbiased historical work.mRb

0 Comments