As the movable type printing press spread across Western Europe in the latter half of the fifteenth century, it’s estimated that Europeans printed around twelve million books. By the eighteenth century, they printed one billion. Such exponential growth began a period, roughly from 1700–1900, during which European culture could “most fully” be described as a print culture, according to the authors of Interacting with Print: Elements of Reading in the Era of Print Saturation.

Interacting with Print, a sort of social history of this period, contains eighteen chapters based on a selection of keywords. This means that the book isn’t intended to be a comprehensive historical accounting of print culture during the period. However, these keyword-based chapters are used to zero in on the cultural practices most instructive for understanding how this deluge of printed material became part of new ways Europeans interacted with each other. Social conventions we now take for granted, such as inscribing a personal message on a book we give to a friend, or a parent and child reading together at bedtime, find their origins here.

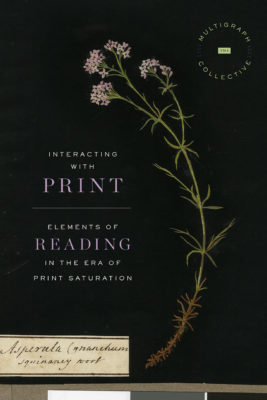

Making this book slightly more interesting than a standard history monograph is the way in which it was written. The authors, twenty-two scholars who refer to themselves as the Multigraph Collective, have taken the topic of “interacting with print” as an opportunity to reflect on the conventions of print culture and authorship at the conceptual level. They describe the book as a “multigraph,” and in the preface describe an elaborate scheme of rotating sessions of drafting and editing, in which all twenty-two scholars eventually had a role in both writing and editing a majority of the chapters.

Interacting with Print

Elements of Reading in the Era of Print Saturation

The Multigraph Collective

The University of Chicago Press

$45.00

cloth

416pp

9780226469140

The focus on social interaction means that the printed materials under analysis are more than just “books,” although chapters called “Binding,” “Marking,” and “Thickening” showcase the importance of personal and professional book customization. Other chapters, such as “Advertising,” “Catalogues,” and “Ephemerality,” indicate how much of the printed material at the centre of social life at the time – such as handbills, tickets, pamphlets, and periodicals that wouldn’t be read again – had a limited lifespan of utility and a disposable quality.

Each chapter affords fascinating insights into how people interacted with print at the time. “Paper” recounts how publishers of children’s books in the late 1700s searched all over Europe for paper that could withstand being used by children. In “Advertising,” we learn of the series of “teaser” advertisements that were rolled out to the public ahead of the publishing of Lord Byron’s Don Juan in 1819. “Proliferation” reveals that our current anxieties about the negative effects of the information age and the internet are not at all new. Conservatives worried that people would become addicted to reading. Others viewed it as a great democratization of information. It all sounds eerily familiar.

Finally, in the epilogue, the authors present one final thought exercise on our epochal shift away from print: throughout the book, the authors use square brackets to make cross-references between chapters and these connections are charted in a networked word cloud that appears in the epilogue. Then, the authors offer a networked word cloud generated by a topic-modelling algorithm, designed to reveal “latent linguistic patterns.” So, who do you trust to better understand the material, the authors or a computer?

Interacting with Print is a decidedly academic book. The added conceptual dimensions are a genuine and admirable attempt to draw the reader into a deeper reflection on humanity’s relationship with communication media. Whether you look upon these experiments as a distraction, a mere curiosity, or in the same grandiloquent, theoretical terms as the authors do will depend on your tolerance for literary and media theory. Nonetheless, anyone who cherishes books and reading will find something of interest in its many depictions of the birth of print culture. mRb

0 Comments