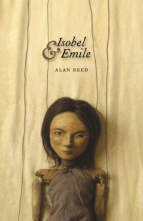

Isobel And Emile

Alan Reed

Coach House Books

$18.95

paper

160pp

9781552452271

The novel is a brief, starkly narrated account of two people trying to put their lives back together after what seems to be – though it is never described – a painful breakup. It opens with a man and a woman at a train station as he departs, leaving his ex behind, and then follows the two of them, in more-or-less alternating chapters, as they go through their blank daily routines. Emile, the young man, moves to another town, finds an old friend in a bar, and spends time there. He returns to his work as a puppeteer. Isobel lives in a small room above a grocery store and convinces its owner, in an almost shockingly sad scene, to let her work there.

The book tracks these simple events very closely, laying them out in precise detail and in short – often very short – sentences, shorn of any ornament. The result of this stripped-down style is the elimination of overt “psychologizing” and the creation of a cool, affectless textual surface:

“It is a busy street. There are people walking down the street and there are people standing in the street. They are wearing scarves. They are huddled inside their jackets. The street is crowded with people huddled inside their jackets.”

Such a flat account is obviously intended to evoke the deadened feeling that follows the collapse of an intimate relationship, the sense that life is mechanical, that one is merely “going through the motions.” To a great extent, it is successful, particularly when connected to repetitive actions such as Isobel’s work at the grocery store. The effect, however, is most poignant in contrast to a series of letters that Isobel writes to Emile, which are interpolated throughout the book. These are written not in the detached tone of the main narration, but in her voice, with all of its human uncertainty:

“I don’t want to be in this place. I don’t want to be the kind of person who lives in this place. But I am. You are what makes me more than this. The way that you touched me, what is left behind in my body.”

The effect of such fervent, naked statements against the primary narrative voice is both startling and engaging.

Reed’s book is also notable for the way it is inhabited by the overarching metaphor of puppetry. Emile stages puppet shows in his room using marionettes that, it is suggested, resemble the novel’s protagonists. He films these shows, recording their movements and interactions. These scenes are artfully described by Reed, conveying something of his character’s discipline and craft, and playing the artificial movements of the figurines against the similarly empty actions of the alienated ex-lovers. If the trope is a little heavy-handed, it is still rather well deployed.

Overall, though Reed’s unwavering commitment to stylistic rigour is not likely to please every reader, for those willing to let go and slide along its carefully honed edge, his novel is sure to linger; in fact, it may be sharp enough to leave marks. mRb

0 Comments