Family madness never gets old, at least in fiction. What distinguishes Jones, Neil Smith’s sophomore novel, is the wit, dark humour, and painful realism that permeates every page. Fans of Smith’s who have waited seven years for his follow-up to Boo (2015) will be shaken up by this heartbreaking, semi-autobiographical novel.

The story opens in the mid-70s with the Jones family transplanted from Montreal to Massachusetts, one of many upheavals that characterize their itinerant lifestyle. “The Caboose,” a one-story addition on the back end of a ramshackle mansion, is their new home. Pal, a hapless alcoholic who cannot hold down a job and disappears for days at a time when he’s on a bender, is reminiscent of Mr. Micawber in David Copperfield, who perennially hoped that “something will turn up.” However, Pal is depraved, sneaking into his thirteen-year-old daughter Abi’s bedroom to “tuck her in.” When Eli stumbles upon them together, he knows he’s witnessed something horrible, but at eleven, he’s too young to understand the implications. Later, he realizes that his father has been sexually abusing his beloved older sister for years, a trauma that will reverberate throughout both their lives. Joy, their mother, knows about the abuse, but does not act to protect her daughter. She’s sharp-tongued and quick to lash out verbally and physically; her children are an inconvenient afterthought. Hugs, cuddles, not to mention care of basic needs, are nonexistent.

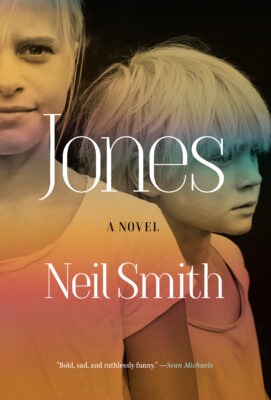

Jones Penguin Random House

Neil Smith

$34.00 pp

Cloth

312pp

9781039001923

The novel follows Abi and Eli from childhood into early adulthood, each chapter representing a different place the family lands: Montreal, Boston, Salt Lake City, Chicago, and then back to Montreal. These constant moves make building friendships, obtaining a consistent education, or putting down roots nearly impossible. The reader witnesses Eli’s love of French, layered throughout the story, and his passion for Montreal, where he’s able to come into his own as a translator. Smith chooses a present-tense narration, which gives each scene an urgent immediacy.

The writing is alive with visceral details, highlighting Smith’s brilliance at depicting the feverish emotions of childhood and adolescence. The dialogue crackles with Abi and Eli’s repartee. The reader is inside every setting, such as the overly chlorinated Natatorium in Verdun that turns the kids’ blonde hair green, or the dark, icy sidewalks in Chicago, where Eli has his paper route.

Understandably, both Eli and Abi love animals more than people. Abi insists she has superpowers, that her soul can leave her body and enter the bodies of animals. “I’m here and not here.” The reader understands why all too well.

While Eli channels his anxiety and obsessive-compulsive behaviour – making lists of Metro stations, amusement-park rides, baseball scores, and more – into the more productive outlet of translation, starting with Le petit prince, Abi spirals downward into addiction and suicidal behaviour.

There is a haunting sadness and inexorable dread echoing throughout Jones, despite its humour. Yet Smith holds pain and hope in precarious suspension with a brilliant stroke concluding the story. The final gut-punch is the dedication to Smith’s late sister, Gail, with a photo of her as a child: flaxen-haired and smiling, one arm arced overhead, as she practices ballet, proudly demonstrating fourth position.mRb

0 Comments