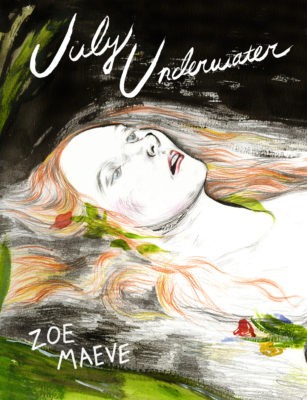

The Conundrum Press logo, a little man in bathing trunks taking a deep dive, is appropriate for Zoe Maeve’s July Underwater. A freeform graphic novel, telling a complex story in relatively few pages, some words, and glorious pictures, the book references Shakespeare, nineteenth-century art, and works from two important twentieth-century writers.

The book’s opening image is Ophelia from Hamlet, drowning in the river, as portrayed by the Pre-Raphaelite painter John Everett Millais. Elizabeth Siddall was the Pre-Raphaelites’ most prominent model, and Millais painted her while she floated in his bathtub, freezing cold in her heavy Victorian costume. July Underwater begins in a bathtub, with Lina, the main character, getting ready for a funeral. We don’t know the cause of death of Alicia, who was Lina’s childhood friend. The reader is given moments from Lina’s life, beginning with her at the funeral, as pieces of a puzzle to put together.

July Underwater Conundrum Press

Zoe Maeve

$20.00

cloth

96pp

9781772620696

Still lifes in colour depicting plants, insects, and seemingly random objects punctuate the main story. Excerpts from two novels, Patricia Highsmith’s The Price of Salt (republished as Carol), and Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse,, are also interspersed throughout. Lina rereads both books when she has time to reflect. The literary and art references are not distracting or snobby; we visualize the scenes from the novels with Lina, and we imagine the effect they had on her. Maeve’s references will please those who already know and love the books and art referenced, and invite the rest of us in to discover them for ourselves.

Maeve relays the flavour of the works quoted. Period details and costumes set the mood. In referencing Highsmith, Woolf, and Millais, she draws parallels between poetry, art, and high culture and key moments in adolescent life: school, sexuality, and drinking on the beach.

The result is cinematic and impressionistic. In panels following Lina on a nighttime drive, or a dip into Lake Ontario at the beach on Toronto Island, gouache paints and inks float over the page as in a dream. The paint calls attention to itself. There are blooms and brushstrokes, along with slightly transparent whites over blacks, plenty of water and plant imagery, even lucid diagrams that plot out a character’s train of thought.

The book does not take long to read – in fact, one would like it to go on longer – but rereading July Underwater is rewarding. Mysteries remain. How much of the author is in her book? What does the “X” on Lina’s shirt signify? Since this is a graphic novel and not a graphic memoir, it is up to the reader to fill in the blanks. July Underwater is an exploration of nostalgia, loss, discovery, and growing up. All of us have gone through it. It doesn’t hammer its points home, but rather touches on them lightly and allows us to come to our own conclusions.mRb

0 Comments