The title of Michael DeForge’s new book, Leaving Richard’s Valley, hints at the deft mix of whimsical and sinister themes within: four animal friends must leave their home in an idyllic, cult-like community and face a Toronto mired in condo construction and gentrification. This is DeForge’s latest Drawn & Quarterly title, and it’s obvious why NPR calls the author “one of the comic-book industry’s most exciting, unpredictable talents.” Leaving Richard’s Valley dissects community, public space, and the dubious line between adventure and exile.

From the first panel of the story, one thing is clear: all the valley animals love someone named Richard. While it takes some time for this supposedly benevolent leader to appear, there’s an uneasy sense that these adorable critters exist under the pernicious rule of a cult ringleader. Valley residents must rub themselves with stones to rid themselves of toxins; potential recruits are separated from their pre-valley families; and the only medical treatment permitted is a special, Richard- approved medicine. This last commandment instigates the rest of the narrative. When Lyle the Racoon becomes deathly ill, he’d rather die than accept help from beyond Richard’s purview. Unwilling to watch their friend expire, Omar the Spider, Neville the Dog, and Ellie Squirrel give Lyle water from outside of the valley. Swift and merciless, Richard shuns the four animals, kicking them out of the valley forever.

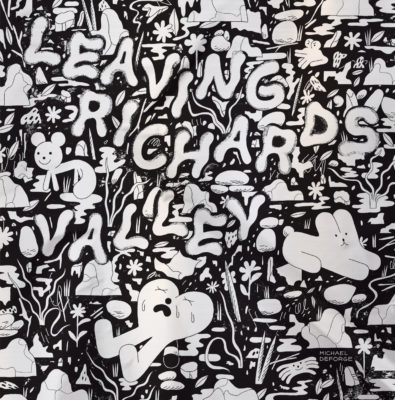

Leaving Richard’s Valley

Michael DeForge

Drawn & Quarterly

$29.95

cloth

480pp

9781770463431

The animals confront the pressing issue of gentrification/condoization and what it means to find a place where you belong. The Marksists buy up properties in the Annex, although the previous owners are “fairly compensated.” DeForge’s book clearly grapples with the harsh reality of evictions, real estate moguls, and skyrocketing rents. Toward the end of the story, Neville wishes the animals could build something together, while Ellie downgrades the utopic dream to something more pragmatic: “I just want a place to sleep.”

DeForge’s drawings mirror this sense of urgency by combining propulsion and stagnation. When the animals are not in a constant state of moving from squat to squat, they are despondent and slumped on the ground, or sluggish and immobile, tripping out on Richard’s hallucinogenic stew. The sparse style used to draw the characters really pops against intricate backgrounds and panoramic cityscapes treated with a beautiful black-and-white photocopy aesthetic.

These literal outcasts are hilarious and endearing, so joining them on their adventure is joyous. As DeForge and the rising cost of living show us, finding a sense of home and belonging can be an odyssey, especially for those deemed outsiders. Feral raccoons and a mock edition of Toronto Life (seven different articles on patios!) might seem like incongruous vessels with which to tackle gentrification, but the worlds inside and outside of the valley become more closely aligned as the tale progresses. In an interview withThe Beat’s Nancy Powell, DeForge aptly states, “I think it’d be hard to be alive right now and not feel as though the world was pretty absurd.” mRb

0 Comments