Life in the Court of Matane is a novel-as-memoir, the third book from Quebec novelist Eric Dupont. Published in 2008 as Bestiaire in French, it is an imaginative meditation on divorce and family life in 1970s Quebec. The boy Eric and his sister begin the story by shuttling back and forth between their parents’ homes until their police officer father – an old-style despot in the vein of Henry VIII – and Anne Boleynesque step-mother take control of the children’s lives, moving them around a series of provincial Quebec towns, never staying in the same place long enough to put down roots. Life in the Court of Matane captures the fear, precariousness, and performance that family life becomes for the siblings. Certain “hammer words” may not be uttered at home anymore, including the name of their mother – sardonically referred to as “Catherine of Aragon” and “Micheline Raymond, professional cook” – until, as high school comes to an end, the siblings choose to remake their lives free of their father’s rule.

Translator Peter McCambridge is no ingénue to the art, having translated seven novels, all from Quebec. McCambridge, who grew up in Ireland and studied modern languages at Cambridge University, has lived in Quebec City since 2003. He directs the website Québec Reads and Baraka Book’s new imprint of Quebec literature in translation, QC Fiction.

I recently spoke with McCambridge about his translation of Life in the Court of Matane and the work of French to English translation in Quebec more generally.

Derek Webster: You’ve called Dupont’s novel Bestiaire, in translation, Life in the Court of Matane. What did you see as the advantages of this more “courtly” title? Was Bestiary taken, for example?

Peter McCambridge: It’s strange but I didn’t ever consider calling the novel Bestiary in English, not even for one second. To my ear, bestiary is a bit dry and doesn’t evoke much in English. Somewhere along the line, you would end up having to explain what a bestiary is and I didn’t want to get into all of that. For me, it was important to have a title that was larger than life, like Dupont’s work, and I like the fact that the title we settled on mixes the personal and the parochial (Matane, a small town in Quebec that international readers will likely never have heard of) with the grand and the political implied by life in the court and affairs of state. Both elements are important as our narrator grows up in the royal court ruled over by his father and his despotic second wife, all to mock-heroic effect.

DW: What were some of the particular challenges of translating this work?

PM: I distinctly remember reading Bestiaire for the very first time in the sunshine of California just after it was published by Marchand de feuilles in 2008. All I could think was, “This is what I want to do with my life … I want to translate this book.” In other words, it’s a translation I started a long time ago – in late 2008 – and that I’ve been thinking about ever since. So I’ve had a long time to think over how or whether to translate this or that. Most of all, the reason I wanted to translate this particular novel is because I feel such an affinity with the author’s voice. I like to think that, if I sat down and wrote a novel of my own one day, I’d sound like Eric Dupont. I love the exaggeration, the way he never describes something in five words if he can do it (beautifully) in ten. Much is made of precision in writing, but I like my washing-machine manuals to be precise; I like my novels to be beautiful and magical and inspiring. And to me, Eric Dupont achieves this by spinning yarns and going off on tangents that feature lots of memorable, juicy details.

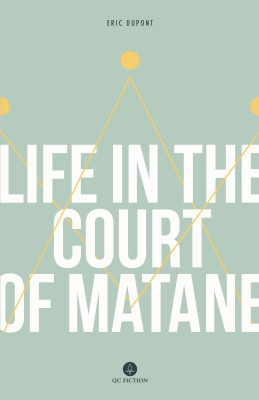

Life in the Court of Matane

Eric Dupont

Translated by Peter McCambridge

QC Fiction

$19.95

paper

262pp

9781771860765

In other words, there was nothing that didn’t feel almost immediately, instinctively right. But translation is an art, not a science. It’s a long series of decisions and lots of people might read my translation and not agree with all of them. But it is what it is. This is my take on how I wanted Eric Dupont’s voice to sound in English. And I’m happy with how it turned out.

DW: Life in the Court of Matane is the first in an ambitious imprint called QC Fiction by Baraka Books, devoted to new Quebec fiction in translation. Has Quebec fiction been undervalued in English Canada and beyond our borders? Do you see a growing interest in Quebec literature on the North American and international stage?

PM: QC Fiction is all about new voices: a new generation of authors and a new generation of translators. If you ask me, there’s little doubt that Quebec fiction hasn’t lived up to its potential in English. We’re aiming to bring out a different type of novel that we hope will appeal to readers all over the world. Idiomatic translations will, of course, be a big part of that, and we’re keen to spend the time it takes reading and finding the right books and then making sure our translations don’t read like translations.

As for a growing interest in Quebec literature on the world stage, it was nice to see Arvida make the Best Translated Book Award shortlist earlier this year. When we get to the point where writers like Nicolas Dickner and Catherine Leroux are regularly making these lists, that will be cause for optimism. But at the minute too many fans of world fiction in translation aren’t picking up books from Quebec. Hopefully that will change soon, and hopefully QC Fiction can help bring about that change.

DW: Last year in the New Yorker, novelist Pasha Malla quoted you as saying “Quebec finds itself too exotic to be easily digested by the Canadian and U.S. market, but not exotic enough to compete with the appeal of something new from Indonesia or Iceland.” How does one go about changing such entrenched notions?

PM: I don’t think the problem is too entrenched as to be irreversible. I don’t think it’s something people consciously do when they walk past a book from Quebec in their local bookstore. But I think that if you were to ask Canadians on the street to name a book from Quebec, more of them would name The Tin Flute than Atavisms or Ru, and that’s a problem. QC Fiction is an international imprint and we’re aiming to put readers in Australia and South Africa in touch with what we consider to be some of the best writing from Quebec at the moment. We’ll see what happens. mRb

0 Comments