Not since the matchbook-sized publication of The Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám has such a sumptuous collection of images been packed into so slim a book. Maleficium is a sybarite’s dream of mid-orient plagues and pleasures, yet it proselytizes moderation.

Written by Martine Desjardins and translated by Fred A. Reed and David Homel, Maleficium has a structure that is simple and repetitive: seven sinners visit a Montreal vicar and, under the sacramental protection of confession, each tells a story so compelling that it moves the vicar to the unpardonable sin of writing them down. It’s the end of the 19th century. Each man has travelled to a capital of the old world – Damascus, Kashmir, Shiraz, Zanzibar – in search of knowledge that will further his profession. Each meets a woman with a cleft palate. She enthrals them. She helps them. She allows them to stroke the silk of success, and then she damns them with their own desires. The spice merchant searching for a spice more fragrant than saffron loses his nose to leprosy; the architect who learns the secret of Shibam’s towers is struck by vertigo so crippling he must

come to the confessional on hands and knees.

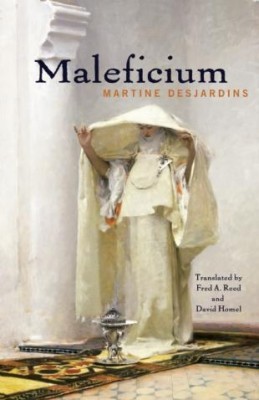

Maleficium

Martine Desjardins

Translated by Fred A. Reed and David Homel

Talonbooks

$14.95

paper

147pp

9780889226807

The seven supplicants each warn the vicar that the woman with the split lip is bringing her curses to him. The confessions are recorded as monologues, so we never hear the clergyman’s voice or feel his anxiety. The prologue discloses how the stories drove the vicar to commit the transgression of recording them, but because we learn this before we hear the stories, the vicar’s worries are placed in the background. This is not a novel of character or dialogue; it does not attempt to be. There is never any question of what will happen in each story, only how. There is tension, given the harelipped woman’s impending arrival at the vicar’s church, but this reader was not entirely satisfied with how that device resolved. The end, however, is left purposefully ambiguous, and supports readings that may appeal to other readers.

Maleficium, then, is a parable about Western ambition as characterized by seven men who, on the eve of the great wars, are hungry for Eastern knowledge. In the guise of the comely woman with the cleft palate, the East protects itself from exploitation as the matador does from a bull – tripping it up and impaling it upon its own horns.

The scarred men return to Montreal, seeking absolution with the harelipped daemoness hot on their heels. When she exacts her final vengeance, it feels as though the snake that has caught its tail is about to swallow itself and disappear. It is not an intimate book, readers will not feel close to the characters, but it is an exquisite rendering of theme. If only all justice was as purposeful and poetic. mRb

0 Comments