George Rideout’s Michel and Ti-Jean is the story of an imagined meeting between two great writers: Michel Tremblay and Jack Kerouac. The meeting takes place during an afternoon in a bar in St. Petersburg, Florida, in 1969, a few months before Kerouac’s death.

As the play begins, we find Jack Kerouac attempting to drink his afternoon and life away while playing a solitary game of pool. He is no longer writing. His main activity appears to be drinking. He is at odds with the world and himself. Enter twenty-seven-year-old Michel Tremblay, fresh off the bus from la belle province, armed with optimism, a copy of his first big hit – Les Belles-sœurs – and a burning desire to meet his literary hero. A hero who, it turns out, has very little interest in meeting anybody, especially another writer… at least not until the beer is bought. Tremblay is undaunted by Kerouac’s less than enthusiastic greeting and ventures onward in his quest to get to know Kerouac, even a little. He is certain that they will understand each other. After all, as Tremblay says to Kerouac: “There aren’t many young boys who dream about books, but we did. And it’s not just the words and the story we love – you wrote about the smell of books and the sound of the pages turning, and the style of the print, and the weight of the book when you held it in your hands and, everything you felt, I felt too.”

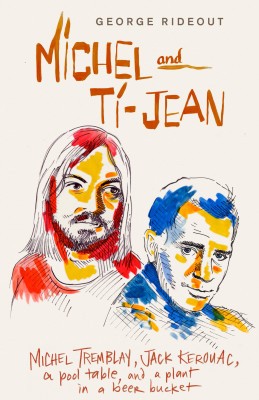

Michel and Ti-Jean

George Rideout

Talonbooks

$17.95

paper

128pp

9780889229020

At its core, this play is about the granting of permission and forgiveness. Tremblay seeks permission to succeed where Jack, his hero, has failed. He wants permission to accept that literary gods are merely human beings, which makes them interesting and exciting, but also messy and complicated, and in Kerouac’s particular case: drunk and very broken. And what he wants most of all is permission to write.

What Kerouac wants from Tremblay is more complicated, but it seems to boil down to forgiveness. Kerouac blames himself for many failings: not being good enough to his mother, not being the “right kind” of son for his father, putting his writing above everything and everyone else. But above all, what he really blames himself for is being alive while his brother, who died at the age of nine, is long dead.

In the end, Tremblay does not need Kerouac’s permission at all. As he puts it, “I write because I am a writer. It’s the only thing I know how to do.” And as the literary world knows, Michel Tremblay continued to write; as for the forgiveness that Ti-Jean seeks, it’s not Michel’s to bestow.

Kerouac needs to forgive himself, but by the end of the play it doesn’t seem that he can. So he keeps drinking and playing pool. Someone once said that Chekhov’s Three Sisters is not a play about three sisters who never make it to Moscow – it’s a play about three sisters who fight like hell to get there. Similarly, Michel and Ti-Jean is not about a man who gave up on himself but, rather, one who is fighting like hell to believe in himself again. mRb

0 Comments