“How many kids can you shoot?” asks Lt.-Gen. the Honourable Roméo Dallaire (ret’d), fixing me with a penetrating blue stare. “Even under the mandate of protecting other people? Or under the international law of self-defence?”

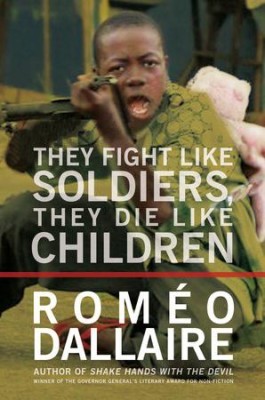

A dilemma worthy of a Greek tragedy, it is one faced by professional soldiers on foreign missions in the developing world. Dallaire’s new book, They Fight Like Soldiers, They Die Like Children, reveals the plight of an estimated 250,000 child soldiers currently used by paramilitary and military organizations around the globe. Most of these children have been abducted or forced by poverty and violence into a ferociously abusive system in which they are drugged, beaten, raped, tortured, and terrified into soldierly obedience. These “little killers” – readily available, low-technology, manipulable – are what Dallaire refers to as a “complete end-to-end weapons system.”

In a small, bare room at Concordia University’s Montreal Institute for Genocide and Human Rights Studies (MIGS), where he is Senior Fellow, Dallaire explains that he became involved in the issue of child combatants following his service as Force Commander of the disastrously underfunded UN peacekeeping mission (UNAMIR) during the 1994 Rwandan Genocide. Dallaire – whose 2003 book Shake Hands With the Devil recounts his experiences during the Genocide, which left him “broken, disillusioned and suicidal” – states that “the child soldier dimension was … experiential from … ’94 where the bulk of the killing was done by youth militia.”

They Fight Like Soldiers, They Die Like Children

The Global Quest to Eradicate the Use of Child Soldiers

Roméo Dallaire

Random House Canada

$34.95

cloth

320pp

9780307355775

Nowhere is Dallaire’s sensitivity to childhood more evident than in the way he focuses on the largely neglected role of girl soldiers. Composing 40% of all child soldiers, the girls set up bivouacs, prepare food, handle logistics, engage in combat, become sex slaves and bush wives. Dallaire underscores that the girls are not only generally more abused, physically and psychologically, than the boys, developing infections and internal injuries due to rape and early childbirth, but – unlike the boys – they are revictimized when their male-dominated communities reject them, upon return, for being “soiled.” “The sin behind it,” says an impassioned Dallaire, “is that the girls feel guilty.”

Astonishingly, in spite of the widespread use of child soldiers, no modern militaries have created any doctrine or “any different equipment to use – nonlethal weapons versus lethal weapons – or training in regards to child soldiers.” Dallaire wants to rectify this, though his approach to the child soldier issue has “created some frictions” with organizations that view the issue through a purely rights-based lens and think he has “militarized the discussion.” But, Dallaire states, “I want to look at how [child soldiers] are being used in the field and how do I make them a liability for the adults who are using them?”

Call it pre-emptive humanitarianism. Dallaire’s commonsensical viewpoint is made all the more compelling by the fact that he has, in the course of the interview, chokingly described the “catastrophic impact” on a professional adult soldier of encountering a child soldier.

The professional soldier’s dilemma might seem a remote one to many Canadians. Why should we get involved if our interests – or our children – are not at stake? Dallaire’s response is instant and fiery:

We have a Charter of human rights that is the law of our nation, right? It doesn’t say for only those living in Canada … It says all humans are equal. So if a child from another country is recognized as a human being then why isn’t that child considered as important as our children? The whole aim is to move – and we have not succeeded yet – the argument from the lowest common denominator which is self-interest to the highest common denominator which is humanity.

If They Fight Like Soldiers gives us a glimpse into the heart of Dallaire’s humanitarianism, Mobilizing the Will to Intervene: Leadership to Prevent Mass Atrocities is all mind, a policy instrument for this humanitarianism. A slim volume co-authored by Dallaire and his MIGS colleagues Frank Chalk, Kyle Matthews, Carla Barqueiro, and Simon Doyle, it is the kind of book that can change the world.

Mobilizing The Will To Intervene: Leadership To Prevent Mass Atrocities

Roméo Dallaire, Frank Chalk, Kyle Matthews, Carla Barqueiro, Simon Doyle

McGill-Queen's University Press

$19.95

paper

191pp

9780773538047

The co-authors make a strong case that the “costs of inaction” are far more damaging in the long run to national interest than preventive action. These costs include, among others, the global security risks associated with the destabilization of entire regions, the increased risk of pandemics, spill-over effects in Canadian and American cities (such as the crippling 2009 protests by Tamils in Toronto), and the immense financial outlay involved in resolving the humanitarian crises that inevitably accompany mass atrocities.

Dallaire, whose frantic appeals for resources and action from the international community during the Rwandan Genocide fell on deaf ears, remarks: “I could not get 200 million dollars to run my mission … Yet within months of the Genocide the international community invested billions in international aid … Leaders of the international community, particularly the developed world, are essentially managing conflicts … there is no fundamental leadership in trying to resolve the conflicts.”

Yet, as Kyle Matthews points out, some have accused the W2I researchers of being “warmongers” for “saying that you sometimes might have to use military to stop people from being murdered,” while others suggest they are “naive.” (Interestingly, conservative commentator Margaret Wente, who initially supported the invasion of Iraq, devoted her March 26, 2011, column in The Globe and Mail to lambasting the “humanitarian imperialism” of Dallaire and others.) The Obama administration, however, has begun to implement the W2I policy recommendations, with President Obama recognizing the prevention of genocide as vital to the US national interest in his 2010 National Security Strategy. And how has the Harper government reacted to the W2I team’s call for systemic change? “We are still following up, but as to date we haven’t had a very positive response,” says Matthews.

Dallaire refers to Canada as a “great nation” with an ease that is utterly devoid of posturing. It is clear why he thinks thus: “We’re among the ten or eleven most powerful nations in the world … We are not a nation that desires to colonize others … Rule of law and human rights are integrated within our values and our ethical and moral references … we’ve mastered technology and we have quite an extraordinary work ethic.”

But it is also evident that he thinks our position as a nation dedicated to “the advancement of humanity,” established during the fifties, has been under threat for some time: “There has been a deliberate retrenchment … as if some mandarins around a decision body of our nation sort of said, you know, ‘why should we get involved in all this?’ Taking this … pragmatic, nearsighted, short term and … local perspective of what Canadians need and what they aspire to.” Instead of a “Kennedy-esque perspective” which could help the country “maximize its potential” for promoting human rights, “what we have articulated on the contrary is meeting our own needs more and more.”

Consider the treatment dealt by Canada to its own child soldier, Omar Khadr, who in spite of being a youth at the time of his capture in Afghanistan, and a Canadian citizen, still languishes in US military detention: “Not only did we lose an opportunity … to apply a convention that we led the world in agreeing to,” says Dallaire, but “we have lost credibility.”

For Dallaire, such narrowness of vision could lead us to the brink of moral catastrophe. “[U]ntil we get a leadership that is able to move us back with even increased capability … into that international sphere, we will be failing humanity. We will be held accountable in history as a country that became egoistic at a time when it could have led.” mRb

0 Comments