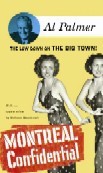

Montreal Confidential

Al Palmer

Véhicule Press

$12.00

paper

165pp

978-1-55065-260-4

According to William Weintraub, who writes an appreciation for this Véhicule reissue, Palmer was a star, “a man who knew all of Montreal’s secrets.” He was also a harbinger of what has become a tradition among Montreal writers of a certain strain – Joe Fiorito and Bill Brownstein come to mind – journalists who’ve used their local newspaper beats as springboards to tackle the unique characteristics of Montreal in book form. Palmer also published a pulp novel – Sugar Puss on Dorchester Street, which now commands as much as $89 on the collector’s circuit. His journalism archives at Concordia University show that he regularly wrote for the papers up to his death in 1971.

It’s not hard to see where the attraction lay in bringing this book, sixty years later, to new generations of readers. Reading Montreal Confidential is like exhuming a long-lost neighbourhood within the city you thought you knew. For the most part, Palmer’s Montreal no longer exists. The street names have been changed in part to accommodate a different cultural history, and the pleasure arena of fancy nightclubs and eateries that was once St. Kit’s (as St. Catherine Street was known to Anglo locals) has been pushed to the edges of downtown by office buildings and brand-name stores.

There is a strong procedural aspect to Palmer’s writing, and, among other things, the approach reveals a period-specific code of interaction that would be unfamiliar to Montrealers today. Palmer will tell you in great detail (and tell is the operative verb here; this book is littered with blunt dos and don’ts) where to take a date, depending on how much money you have to spend, and how much to tip all levels of restaurant and nightclub staff. If you’re a girl moving to Montreal, he’ll tell you where to stay on your first night in town, and where to go afterwards. If you’re looking for beer, Palmer’s got advice on that as well.

When Palmer’s colourful period slang soars – waiters are “tray toters who served the stupor suds”; World War II is the “Late Hate” – his habit of telling readers what to do can feel like a bona fide insider’s view of the big town. There are more than a few occasions, however, on which Palmer spends pages painstakingly documenting, say, the careers of various headwaiters across the city, and one has to wonder if this degree of detail would have been advisable even when the book was first published.

Either way, Palmer certainly knew this town inside and out, and Montreal Confidential is an amusing and frequently intriguing snapshot of a time when Anglos had a stronger foothold in the city’s business community and nightlife. Véhicule Press’ venture into reissuing Montreal’s cultural history ought to be applauded. Palmer, after all, belongs to the lineage of writers who currently fill this city with words, and one would hope that the regional independents would take even greater interest in reissuing the works of more long-gone local talents.

mRb

0 Comments