“Ididn’t write Motherhouse with the intention of challenging the current mainstream approach to performance in Canadian theatre, but that’s what seems to have happened.” That’s how David Fennario introduces his latest play, Motherhouse: with a bold – and merited – assessment of its potential.

The script of Motherhouse tells a compelling story. It paints a picture of working-class Verdun during World War I and the impact the war had on the community, particularly the women at home, left to labour in the British Munitions Supply Factory. Our narrator is a woman named Lillabit, although it seems Fennario’s true protagonist is the city of Verdun, itself a tragic hero of the Great War, and a site of warfare: close-knit conflict between the poor of Verdun and wealthy of Westmount; between the French and English (“Very important to learn certain nouns right away when you’re working with gunpowder”); between Protestants and Catholics (“the kind of job a peasoup or a paddy would get, not a Protestant”); between protestors and police (“if you’re sick or hurt or pregnant, they don’t care but they don’t like you peeing in their van”).

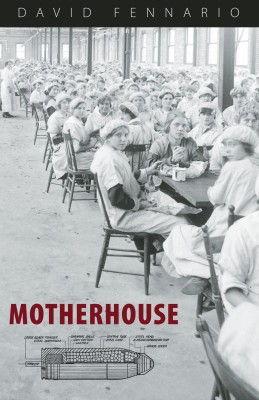

Motherhouse

David Fennario

Talonbooks

$17.95

paper

128pp

9780889228281

While there is plenty of new work on Canadian stages that explores political content and new forms of audience engagement, it is rare in mainstream theatre to encounter a play that actively makes the personal political and, moreover, so confidently follows Brechtian traditions. That is, it privileges a critical (anti-war, anti-capitalist) message over “objective” and “universal” modes of storytelling that handhold the audience through catharsis. Lillabit often reminds us that she’s a vehicle for “the playwright”; the audience is not even introduced to the munitions factory, the setting of the play’s main action, until a third of the way through the work, after Lillabit has adequately monologued about the social, political, and economic context. Mainstream work has not trained Canadian audiences for this style of political work.

Fennario implicates the audience. We are reminded throughout the play that the politics are not simply history, but an ongoing reality: the striking workers during World War I were the 1910s incarnation of Verdun’s working class revolutionary spirit, which continues to manifest through movements like the 1970s protests for tenants’ rights and the massive student protests against tuition hikes in 2012.

Although he claims it wasn’t his explicit intention, it is clear that with Motherhouse Fennario is working against the practices in theatre-making that serve to depoliticize creative output. He tasks us to tell real stories that can facilitate change: “No more pretending to be someone else on or offstage.” The play tasks those who stage it to reimagine the relationship between actor and character, artist and audience. Just as Lillabit’s anti-war storytelling interrupts the militaristic, romanticized, red poppy-filled narrative of World War I that permeates Canadiana, Fennario’s script is an attempt to interrupt dominant practices of theatre-making. It will be up to others in the process – producers, directors, designers, actors, and audiences – to determine if the politicization in Motherhouse can, in practice, successfully carry forth to the rehearsal room, stage, and streets, or if it will remain on the page. mRb

i love this man and his work.