Anaïs Barbeau-Lavalette wants readers to think about what the poverty of East End Montreal is like for children – how unpleasant it is and how much they suffer. Inspired by her experiences as a Big Sisters mentor to a girl in Hochelaga-Maisonneuve, child star turned film director Barbeau-Lavalette originally published her bleak and solemn first novel Neighbourhood Watch in 2010 under the title Je voudrais qu’on m’efface. It appears here in a clean translation by Rhonda Mullins, whose English prose almost never draws attention to itself as a translated text.

Three pre-teen characters are the hub of the novel, along with their parents, who live next to one another in a low-rent apartment block: Roxane, who is neglected by her mother Louise, a brutally battered alcoholic who does sex work in the house; Kevin, whose soon-to-be-unemployed father Steve doubles as Big, the local lutte de sous-sol wrestling champ; and the truly doomed Mélissa, who begins the novel by emancipating herself from her IV-drug-using mother Meg, a street-corner sex worker, by getting a restraining order against her, only to discover that being a mom to her two younger brothers while still herself a child is more than she can handle.

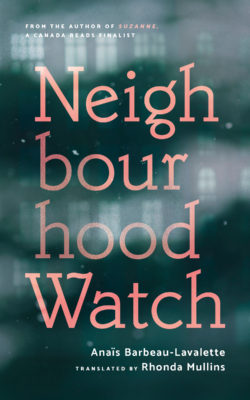

Neighbourhood Watch

Anaïs Barbeau-Lavalette

Translated by Rhonda Mullins

Coach House Books

$29.95

paper

128pp

9781552454176

Notably absent within the novel is curiosity. Both adult women in the novel suffer addiction (one to alcohol, the other to IV drugs) and are forced to do sex work to support themselves, yet the book shows no interest in how these women arrived at such extremes of human experience.

But as we watch the children of the novel endure trauma after trauma, readers may wonder why we don’t hear about the adults’ traumas – about how poverty works at the human level, and how it leaves lasting wounds. What are the pains Louise, Meg, and Steve have suffered, and how are they passing those traumas on to their children? What is the nature of the darkness that encroaches when Louise considers not drinking for a day?

Barbeau-Lavalette stocks her novel with addictions but doesn’t ask how any of the characters suffering that state arrived there, or interrogate the connection between addiction, poverty, and the trauma she’s rendering in such exploitative detail it tempts the accusation of “poverty porn.” These are failures of character above all: Barbeau-Lavalette seems to have reflected more deeply on the miseries she inflicts upon her characters than about who these characters are and why they do the things they do, leaving the reader at a remove that largely impedes emotional access to them as whole people.

Barbeau-Lavalette is at her best rendering the emotional world of parent-child relationships. Steve’s fraught role as a failing man idolized by his son is the most complex, charming, and occasionally subtle part of Neighbourhood Watch, while Roxane’s relationship with Louise and her father, Marc, himself in early recovery from alcoholism, is depicted with far more emotional force than the parents’ addiction. But though the novel ends with a few notes of hope amid the grimness, there’s little sense of what will happen to these kids we’ve been made to watch suffer, beyond a clear sense that they will suffer again. It’s as though the author is incurious not just about the causes of the poverty and addiction by which her characters’ worlds are circumscribed, but also about the full breadth of the characters themselves. mRb

0 Comments