The backyard is empty now, except for a few pieces of trash. There are piles of old white buckets, their insides crusted grey with leftover cement. A big muddy suitcase, crawling with pill bugs, sits by the shed. The bikes are carcasses, stripped of wheels and chains. Even the wooden fence is missing slats.

But on summery Friday nights in 2010 and 2011, when Guillaume Morissette lived at 4562 Saint-Dominique, as many as 200 people would flock to this muddy square of grass for free outdoor film screenings. The screen was made of two-by-fours and a bit of recycled cloth. Most of the chairs had been gleaned from a restaurant that had gone out of business. Morissette and his roommates bought so much Pabst Blue Ribbon at the local dépanneur that the owner gave them a discount. They resold it illegally, at a markup, out of a plain brown suitcase. If the cops showed up, the suitcase would be zipped shut and tossed out of sight.

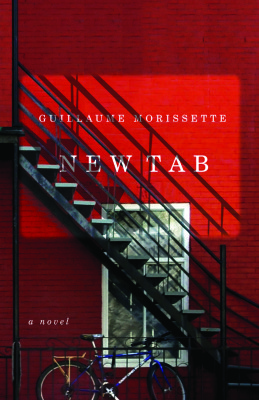

New Tab

Guillaume Morissette

Esplanade Books

$19.95

paper

164pp

9781550653724

He didn’t always feel this way about literature. No one inspired him to read books as he was growing up in Jonquière. The literature that was taught in school seemed distant from his experience; books were written in a French that hardly resembled the joual he spoke at home and on the street. “Video games were a medium I felt close to as a teenager,” he said. As a young adult, he moved to Quebec City, to work in game design.

But in 2008, he fell into a deep depression. The next year, still suffering, he moved to Montreal, into a primarily Anglophone community, and began to pick up English books by authors like Miranda July, Jean Rhys, Mary Robison, and Jack Kerouac. “It made me laugh and consoled me,” he said. “I found myself recognizing my own problems in these writers’ plight.”

New Tab opens with Thomas cut loose from all sense of community. He is moving into a new apartment with strangers from Craigslist, whose lives he discovers by “stalking” them on Facebook. At work, he creates documents that allow programmers and producers to work on the same project without communicating face-to-face. His parents have given up on being parents, preferring the company of their possessions to that of people. “I think they’re going feral,” Thomas muses to one of his friends. “Soon they’ll eat the dog.”

Yet Thomas’s own social life is devoid of real connection. He spends hours chatting on Facebook, and gets drunk at parties so he doesn’t have to engage with the “stir-fry mix of personality traits.” He jokes with Romy, the woman he may or may not be dating, that they should register a patent for “lonely partying.”

Although the book eschews any sort of traditional narrative arc – some sections feel like the collected tweets of Guillaume Morissette – Thomas’s interest in Romy gives the book its story. At first, she is an Internet ghost, a person who exists to him only through email and Facebook. But then she appears at one of the backyard film screenings, and they strike up a friendship based on their shared alienation. He writes poems with titles like “All My Relationships Are Ambiguous Relationships” and “I Am Sorry You Are a Poem, Poem”; she writes stories about “characters who have no ambition and think dating in Montreal is the absolute worst.” Every so often, there are flickers of true companionship, but overall, the relationship can be summed up in a single sad sentence: “We slept in my bed, but not together.”

Morissette may have captured the utter loneliness of the dot-com generation, but he does not see the Internet as a source of isolation. Nor does he see New Tab as critical of our dependence on the virtual world. “It embraces the Internet as a profoundly transformative experience,” he said. “I don’t feel alone. When you’re at parties, you’re at the mercy of other people. On the Internet, there’s some form of protection.”

The illusion of safety that the Internet provides is everywhere in his writing. Intimate details are revealed in quirky sections, often no more than one or two sentences long, in the same way that millions of people reveal their most private longings and rejections through Facebook status updates. Some of these sentences are deep (“entire lives archived on the internet like garbage piled up in a landfill”), some ridiculous (“rice”), and others are simply strange: Thomas imagines his penis as a “take-a-penny, leave-a-penny” tray, and compares his pain to that of a sea turtle.

“My poems weren’t very poetic, they were more like emails gone wrong,” Morissette explained. And if the prose in New Tab sometimes feels improvised or offhand, it was intentional on his part: he spent four or five months just trying to establish the tone of his novel, reworking the same material until it felt right to him.

His interest in experimentation was what led him to writing in English in the first place. “English is easier to play with than French,” he said. “It’s like this Lego language. You can make a word out of anything.” His writing is at its most inventive when he writes about depression:

I wanted reality to go away for a while, make me miss it a little. Reality was a kind of insomnia, always there, just there, annoyingly there, in my bed, at the park, inside every raccoon, behind movie stars in movie trailers, there, being, occurring, fluctuating, not telling me what it wanted from me, giving me the silent treatment, a kind of torture.

Even though New Tab is a novel haunted by depression and loneliness, it is a record of Morissette’s self-reinvention: he changed jobs and languages during the year and a half spent living at 4562 Saint-Dominique. He discovered a creative community among the people who attended the backyard film screenings. He found an escape from his depression.

The chameleon-like ease with which Morissette has been able to reshape his identity does come with some disadvantages. “Since I chose to write in English, I’m doomed to

be ignored by the French Canadian community,” he said. That said, he is happy with the book and the changes it documents: it was “liberating to write honestly, openly, almost violently about personal experience.” mRb

0 Comments