There is a whole branch of philosophy about the Just War, but Dimitri Nasrallah remains sceptical. “Ultimately, war is chaos,” the Montreal author says. “The vast majority of people are caught in the middle. They’re waiting for the shelling to die down so they can go to the store, hoping that the electricity doesn’t cut off long enough for their food to go bad or that a bullet doesn’t come through their window.”

Niko, Nasrallah’s second novel, begins with this chaos in the form of the Lebanese Civil War. The book comes out this April, and, given recent world events, it couldn’t be more timely.

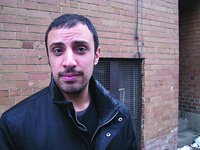

We met to discuss Niko over a beer at a Little Burgundy café. Easygoing and friendly, he admits that he is usually the one doing the interviewing. When not working on his novels – including what he calls his “mistress novel,” which he writes when his main project isn’t going well – he works as the electronic music editor at the Canadian magazine Exclaim! and contributes to a variety of publications. But it is for his fiction that he has gotten the most attention. His first novel, Blackbodying, won the 2005 McAuslan First Book Prize from the Quebec Writers’ Federation and his story “The Forested Knolls of Elbasan” won the 2006 Quebec Writing Competition.

Niko

Dimitri Nasrallah

Véhicule Press

$18.95

paper

241pp

9781550653113

We first meet the novel’s eponymous protagonist when he is six years old. His days are unstructured, as the schools have closed because of the war, and he spends his time watching television, hunting flies around the family’s small apartment, and hanging out with his father Antoine, whose camera store has been bombed. Niko’s mother is expecting another child, and she spends her day working as a writer, trying to keep her idle husband and son from breaking her concentration.

The Beirut scenes alternate between boredom and the meaningless acts of cruelty that punctuate it. As Niko and Antoine drive home from church one Sunday, they are forced to watch as the teenagers manning a checkpoint tie a plastic bag around a captive’s neck “so that it inflates and deflates with every breath, like a giant heart.” The teenagers laugh as he tries to breathe.

This kind of detail captures the war-torn city in a few deft strokes. Early on, we begin to feel for the characters caught in this landscape who Nasrallah describes as being on “the side of ordinariness.” We are to school. But they are barred from establishing themselves anywhere. So when Antoine’s sister-in-law offers to take in Niko while Antoine gets himself back on his feet, Antoine agrees.

Niko joins his uncle and aunt, Sami and Yvonne, in their small apartment in Montreal North. The boy resists settling in, convinced that his father will return at any moment to whisk him away from the desolate life of a new immigrant. In the meantime, he turns to petty crime to keep himself amused.

Antoine keeps moving without his son, trying to scrape together enough money to fulfill his role as Niko’s father once again. Nasrallah was particularly interested in exploring father-son relationships, he says, because “around the eighth or ninth draft I realized I was going to become a father myself, and then around the twelfth draft, my kid was born.”

By alternating the focus from one character’s inner life to another’s, Nasrallah creates a series of cliffhangers which propel the story forward. But the pleasure of reading Niko comes from more than just its fast pace. In this novel, Nasrallah has created complete worlds that you carry around in your head after you put the book down, worlds to which you want to return. What makes these settings so enticing is the way they are built up around the characters.

There are, however, some character-environment pairings that are more interesting than others. For example, Niko’s desolate early life in Montreal seems predictable in comparison with his father’s adventures.

Antoine finds work as a sailor, which takes him from North Africa to the coast of South America, where he gets shipwrecked. The scenes that take place on both sides of the Atlantic – Nasrallah calls them “mythic” and “surrealistic” – show us better than anything else in the book that we are in the hands of a master storyteller.

He wonderfully captures the sense of loss that accompanies the immigrant experience:

Everywhere around him, the street lamps flicker on, turning the island into a constellation of stars, a minor universe in the middle of the sea. Had he arrived here without his problems, Antoine would have very much enjoyed the slow pace of this idyllic island. Maybe in another time, he and his wife and the boy could have vacationed here.

“I don’t consider this an immigrant novel,” Nasrallah said when I asked him about the Lebanese community’s reaction to Niko. “If they see their own stories in it, fine. It’s not an anthropological book. I’ve never expected it to be representative of the story of a community.”

The author’s own story, though, can be read into some parts of the plot. Nasrallah was born in 1977 in Lebanon, during the civil war, and his childhood was spent trying to escape the violence. His family moved to Kuwait temporarily during “the more explosive parts of the war,” and then to Athens, where his father’s advertising company had been relocated. “There was this whole economy in the countries around Lebanon that took shape around these people waiting for the war to end,” Nasrallah said. “We were part of that for a while.”

He arrived in Greece in time to start kindergarten at an American international school, and Nasrallah felt at home there. “That school was a collection of foreigners,” he recalled. “You didn’t really feel like an outsider there because everyone was an outsider.” But because of Greek immigration laws, the Nasrallah family wasn’t allowed to set up their own life there, so they moved again, this time to Canada via Dubai.

Nasrallah’s arrival in Montreal at age eleven was more difficult. He didn’t speak French, having learned English at school in Greece and basic Arabic in Lebanon, but he landed in a French school because of Bill 101. This left him feeling mute and excluded, a position he portrays in Niko. Nasrallah describes the book as dealing with “the manifestations of alienation that come with being in an environment that’s not your own.”

He hadn’t intended to write about his own story. In 2005, after Blackbodying came out with DC Books, an editor at another publishing house suggested he write about his roots. “This was not something I took well,” Nasrallah said. At the time, he had been working on what he terms a “speculative, Kurt Vonnegut-style story,” and he had no interest in writing about his origins. “But I figured the question was going to keep coming up, so I had a go at it, and for the longest time it didn’t work.”

Six years and fourteen drafts later, it works. mRb

0 Comments