In her latest short story collection, Sarah Gilbert, a longtime resident of Mile End, delves into the recent wave of gentrification in the area from the perspective of multiple residents who have been forced to change with their neighbourhood. As rent increases and novel storefronts bring newcomers to the community, Gilbert pulls at the tensions between old versus new, culture versus commodification. As she jumps between personas – artist and businessperson, child and parent, professor and student, landlord and tenant – Gilbert challenges the meanings of home and community. While her characters navigate life in the Mile End, she considers far more than just the consequences of gentrification: How do the places we inhabit shape our relationships?

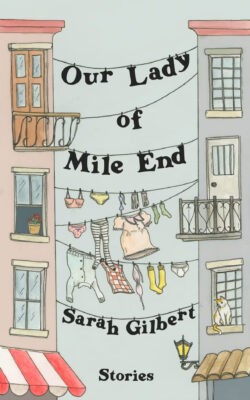

Our Lady of Mile End

Sarah Gilbert

Anvil Press

$20.00

paper

208pp

9781772142143

As little Frederique clutches a Harry Potter book on her way to and from school, the physical space of Mile End is further understood through childlike wonder. “In books the people who noticed children and animals turned out to be magic. In real life, they were homeless. Serge, who slept on a cardboard mat outside the grocery store, bowed to Fred when her mom gave him a loonie.” Fred’s environment heavily contributes to a startling loss of innocence, though it also teaches her independence and later provides a common ground for her family. Gilbert’s striking contrast between Fred’s imagination and the harsh realities of “progress” suggests Mile End is crucial to Fred’s coming-of-age story. The neighbourhood is fundamentally linked to her sense of discovery; the growth of one is intrinsically tied to that of the other.

Gilbert’s work is a mixture of quippy dialogue, tight prose, and a narrative style that reads like a love letter to Mile End. In “Banquet,” the neighbourhood rallies against gentrification. The sidewalk reads “NOSTALGIE; ANGER; ESPOIR; SOLUTIONS? ADAPTATION.” A banner says, “MILE END IS DEAD. THANK YOU FOR YOUR BUSINESS.” A musician eulogizes the neighbourhood in a song lyric made up of the names of the evicted. What was once signalled by Gilbert through outrageous prices, busy supermarkets, or struggling artists finally has a name – gentrification – and it is displayed across a surround-sound street festival. One woman faces the music while harbouring a secret: she will soon be another name on the list of the displaced. Bri scans the crowd below the banners in vain for the faces she has grown so used to. “Over the years, many familiar faces had just evaporated.” This news has an air of devastating finality that is redeemed only by the quantity of lines, expressing sincere adoration for the space.

Despite a heavy overtone of change, this story becomes an encyclopedia of Bri’s favourite parts of Mile End. “She fell in love and made a vow to the neighbourhood.” The community members who hold on to their versions of Mile End do so with a loyalty and dedication reminiscent of a loving relationship. In a place full of friends, diversity, and art, the worst consequence of gentrification in the Mile End is not a material change, but rather it is the crack in the neighbourhood’s collective memory. Gilbert emphasizes this early in the book as she describes an old hatmaker who wonders what happened to the schmatta industry. She looks at the storefront that had been her hat factory for seventy-five years and hears passersby wonder, “That new atelier, didn’t that used to be something else?”

Our Lady of Mile End is an ode to the neighbourhood’s cultural legacy, the soul of which is written into all of Gilbert’s characters. This soul is in the resilience of children who collect bottles from the street, and in an artist who cleans the houses of wealthier neighbours, all the while using their dust bunnies for textile art. It is in the defiance of a witty hatmaker who says, “I make hats, not speeches,” and wistfully remembers her Mile End. While her Mile End characters are central to each of the short stories, Sarah Gilbert expertly relays how their experiences overlap with poignancy, humour, and wisdom.mRb

0 Comments