Do Not Enter My Soul in Your Shoes

Natasha Kanapé Fontaine

Translated by Howard Scott

Mawenzi House

$18.95

paper

72pp

9781927494516

Fontaine’s syntax is consistently surprising, her imagery sensual and immediate. Lines like “Your teeth laced up my vertebrae / your eyes are muddled with cedar / our bed of dead leaves is furrowed our hunts / purged of your cider” demand to be sunk into. She tackles big, expansive emotions but sidesteps cliché, always returning to the precise detail, the “shore / braided with white pearls.” A crucial voice.

This World We Invented

Carolyn Marie Souaid

Brick Books

$20.00

paper

77pp

9781771313544

The second section, which shares the book’s title, documents chaos, decline, and a sense of unease, but also hopefulness in parenthood, recovery, and pressing on. Souaid witnesses the world’s messiness without reaching for tidy solutions, recognizing instead that “There’s just one crested wave. / And then another, and another.” This collection pivots and turns, speaking from diverse vantage points, illustrating a line from “Collage”: “What you need to say has many rooms.”

Mockingbird

Derek Webster

Véhicule Press

$18.00

paper

80pp

9781550654264

Like the titular mockingbird, Webster echoes the voices of others, referencing Larkin, Hughes, and Dickinson, and nodding to traditional forms. He frequently employs rhyming couplets; these are most satisfying when their rhymes are somewhat unpredictable – “Woodsmoke’s listless curlicue— / what’s left of what you thought you knew” reads musically over “Rat moving at your feet / A car in the street,” for example. Webster’s vision is at its starkest and loveliest in the book’s penultimate section, where he turns his eye to an idiosyncratic set of birdwatcher’s field notes, an eclipse, a pelican’s “beauty’s folded awkwardness,” and “mist like a cat creeping up the lawn” – images that retain their mystery, allowing us to draw our own conclusions.

A Clearing

Louise Carson

Signature Editions

$14.95

paper

96pp

9781927426630

Despite occasional moments of heavy handedness, many of these poems show a knack for saying just enough. Trained as a musician, Carson experiments with different tempos and capitalizes on the possibilities of variation and repetition. Her carefully considered rhythms range from breathless lines that spill into one another, to shorter ones that unfold slowly, emphasizing silences and white space on the page. Carson’s concise and elegant descriptions are most memorable when they push into a subtle strangeness – the man who steps into the shower, “swimming goggles adjusted”; the woman who “asks everyone she meets: / did you bring me my new face? Did you bring me one with a bright / curved beak?” Carson uses a matter-of-fact tone to avoid oversentimentality, as in “29 words on solitude”: “Sometimes chosen, often not. / Society can tell. / I’ve got emotional leprosy. / Bits of me are dropping off. / Not so bad. When I walk out, / I can hear my bell.” These poems meditate on the potential to be found in small moments, in personal “clearings,” as Carson articulates in “between times”: “in between / is when / I sail the seas.”

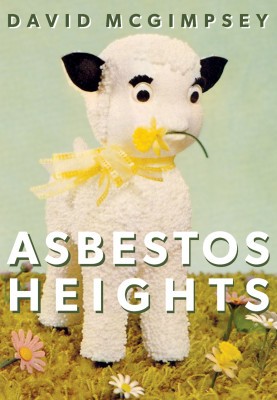

Asbestos Heights

David McGimpsey

Coach House Books

$17.95

paper

96pp

9781552453094

At the same time, McGimpsey is interested in sincere emotional expression, whether it comes from a poem or a Taylor Swift song. There are many self- deprecating and bittersweet moments here, too, whether in the form of a therapist who couldn’t be less interested in her client’s poetry, or a quiet memory: “My father, at ninety-nine, could not / recognize his favourite Yankees’ faces / but knew their body shapes, averages / and what they did their last time at bat.”

The writer’s attempts to be “classy” unravel over the course of this set of “canonical notebooks,” as signalled by the titles alone – we go from “Nasturtium” to “You may remember me from the smallpress Canadian poetry titles Sugar Shack Parson and Midnight Call to Petawawa.” The effect is dizzying, in a good way. McGimpsey is pure reading pleasure. mRb

0 Comments