Mission Creep

Joshua Trotter

Coach House Books

$18.95

paper

104pp

9781552453193

Using the CIA’s “Human Resource Exploitation” Training Manual as source material, Trotter tortures the text until it gives up half-truths and near-revelations, rendered in thick blocks of sentences that fade in and out of coherence like a radio dial being spun. The flurry of juxtapositions that emerges is by turns silly and disquieting, like this from “The Ghost Is Clear”:

… Once strengths and weaknesses have been identified it is possible to make long-term plantations. Yesterday a state of maximum inefficiency, tomorrow a co-operative attitude, plus favourable conditions for performance art. Orgasm. Self-pity. Purell. Is that you crying? Lick me in the eyes and ask me again. Do you feel the same as me twice removed?

The text’s CIA origins float to the surface only now and then, like veiled threats, but for the most part references to terrorism and wiretaps are delivered with the same emphasis as those to Evel Knievel and Scrabble; they are all part of the same unmodulated onslaught of language. The repetition of sounds and the near-familiarity of phrases offer one kind of satisfaction, while denying another. For all its chaos, Mission Creep confirms that Trotter’s strength is his willingness to work within convention, whether that convention is defined by tradition or his own devious imagination.

The Unlit Path Behind the House

Margo Wheaton

McGill-Queen’s University Press

$16.95

paper

96pp

9780773546776

Wheaton uses pathetic fallacy to create startling images of the moon (“compulsively telling its story”), the rain (“drenching the earth … as if to heal / the dryness here”), and the woods in “Pause”:

You’re certain that within

this dark population of resolute pines

and maniacal roots,

in the damp austerity

that’s been made by days

of exhalations,

is a name for the loneliness

wrapped inside the torn cloth

of the train whistle’s cry,

Subtler than straight personification, pathetic fallacy can be an inventive way to create atmosphere within a poem, but cumulatively it flattens this collection’s visual field. A neighbour rescuing peonies from the garden before rain or a homeless person sleeping in a parking lot seem as symbolic as a sunset. Blurring the line between people and things creates distance where intimacy was intended. The poems are strongest when they look into the darkness unflinchingly: a long elegy for a friend killed in a car accident, anchored by the specificities of friendship and grief, is among the book’s strongest moments. Where metaphors are deployed to create drama, the same grief doesn’t ring as true.

When Carmine Starnino uses personification in his poems, he doesn’t project emotional states onto objects so much as imagine the exterior world’s sardonic back-talk. “It’s style (or whatever unique intuition a poet brings to his diction, rhythm, and syntax) that vivifies raw data into poetry,” the poet argued in a 2004 interview in The Danforth Review, and Starnino’s poetry embodies that argument. His meaty diction and formal rigour assert that the way of saying is as urgent as the “raw data” being said.

Leviathan

Carmine Starnino

Gaspereau Press

$18.95

paper

80pp

9781554471546

The tension between fathers and sons comes to symbolize a man’s struggle to shape his identity by embracing and rejecting given models. In the long elegy “San Pellegrino,” a glass of water (half full) is the window through which a father is remembered during his final days as an “epic-snorer, inveterate jaywalker,” “a ditherer, a born quitter.” The incessant repetition of the er sound, which ends almost every line, gives the poem a meditative and prayerful rhythm, but also a low growl – perhaps a moan of frustration at the fact that our parents so often embody an outdated ethos that fills us with both nostalgia and shame.

There is a pleasure in watching Starnino, who enjoys throwing his masculine weight around as a critic, wrestle with these complexities. More than tackling, he touches, with a wit and nuance often lacking from the ferocious defenses of poetic orthodoxy he deploys in his criticism. He confirms here that, if nothing else, a real man knows what his leaf-blower compensates for.

In addition to his work as a poet and critic, Starnino serves as editor of Signal Editions, and one can see his fingerprints on Michael Prior’s debut collection, Model Disciple, which they publish this spring. Prior’s formal strength and self-conscious wit recall his editor’s. His inventive approaches to self-revelation help break his work out of a purely confessional mode and give it refreshing emotional range.

Model Disciple

Michael Prior

Véhicule Press

$17.95

paper

96pp

9781550654394

The collection is anchored by a long narrative poem written in iambic pentameter that tells the story of a road trip to Tashme and other sites of Japanese internment by a Japanese Canadian grandfather and his grandson, who feels the unbridgeable distance between their experiences of the trip as they tour the former camp:

their siding split and cobwebbed. I wonder

aloud if they could be originals.

He stands on his toes, shades his eyes, and tries

to glimpse inside through the dirty window.

I don’t know. Can’t he recall anything?

“Tashme” demonstrates how form and metre can contain a poem. Here, the form is a levy against a flood of love and horror the speaker feels in the face of his grandparents’ traumatic history. It braces him against the possibility that memory is one destination to which we must travel alone.

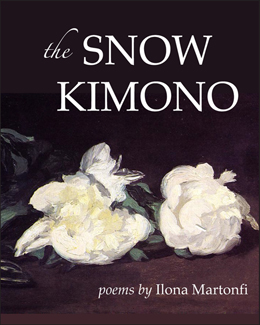

The Snow Kimono

Ilona Martonfi

Inanna Publications

$18.95

paper

128pp

9781771332576

Atmospheric and spare, most poems in the collection consist of images strung together like beads, as though their speakers are trying to piece together memories one object at a time. “The cellar room,” which remembers a World War II air raid over Budapest, is representative:

Candles and kerosene lamps dispel darkness.

On the oak table: krumplileves — potato soup. Corn bread.

Here in my childhood house. Christmas Eve, 1944:

a besieged Budapest. Snow-covered boulevards.

Steep clay stone roof. Chimney. The woodbox stacked

with logs and coal.

A bridge in Guernica; a city street in eighteenth-century Venice; the unhappy home of a husband and his wife, whose body has been exhumed from a Dutch bog nearly two thousand years later: the settings Martonfi draws are vivid even when they are imagined. The poet’s ability to take us from place to place gives the collection a telescopic sensibility, within which notions of here and there, now and then, shift, suggesting that what is distant can become, through a slight change in light, suddenly intimate. mRb

0 Comments