To enter the world of Jacob Wren’s novel Polyamorous Love Song is to enter a bizarre yet compelling dreamscape, a parallel universe where everyone is an artist (regardless of whether they produce physical artwork or not) and where revolutionaries don mascot uniforms and risk death for their cause, the politics of which are left ambiguous. A thrilling though at times disturbing read, it is flirtatious and experimental, unconcerned with literary convention, and unapologetically playful yet utterly serious.

One of several narrators – the one who is writing this book and possibly also the one who shares a first name with the author – has a theory about artists: they are “not necessarily the most creative or inspired individuals in any given community.” Rather, they are “those individuals most willing to exploit their own creativity and inspiration, most willing to gain personal profit from their unconscious and its emanations, those with the most missionary zeal for the dissemination of their own idiosyncratic perspectives.”

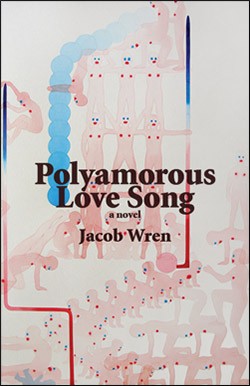

Polyamorous Love Song

Jacob Wren

Book Thug

$23.00

paper

192pp

9781771660303

First we meet Filmmaker A, who, after a “crisis of faith,” goes on to found a new type of filmmaking. Based on her example, “‘filmmaking’ becomes slang for scripting your life as if it were a movie, and then, throughout the process of such scripting, enacting quite naturally and casually each of the scenes you write.” The line between life and art becomes increasingly blurred: “This is the film,” Filmmaker A yells at her girlfriend Silvia during an argument. “What we’re doing now, this is the film.”

Parallel to and overlapping with the narrative of Filmmaker A is the story of the Mascot Front, a “shadow organization” of revolutionaries who live their lives mainly in uniform, and a group of new filmmaking devotees, individuals who drink a daily cocktail that allows them to remember phone numbers, suppress jealousy, and remain in a state of sexual arousal for what seems like nearly around-the-clock sex with other members of the group.

Though the prose could arguably stand the occasional tightening, its looseness and quasi stream of consciousness is also part of the appeal. This story wouldn’t be properly expressed in perfectly wrought prose, but only in the imperfectly beautiful, in the fragmented, honest, and raw. Polyamorous Love Song isn’t a book for everyone, but it’s likely to appeal to fans of art theory, performance art, and Chris Kraus, to those who like their narratives obscure and bold with a smattering of sex and violence.

0 Comments