Ravenscrag bills itself as a story about the mansion above McGill University where the CIA ran LSD and electroshock experiments in the 1950s and 1960s, which certainly sounds appealing, but it is in fact the story of an academic having a 60,000-word mental breakdown before infiltrating an asylum to shoot people with a toy gun. Published in French as Pourquoi Bologne, Alain Farah’s book, impeccably translated by Lazer Lederhendler, reconstructs a mental breakdown (that may have been exacerbated in the mansion) in short disconnected chapters that shift topic and time period, occasionally descending into hallucinatory paranoiac episodes.

Writing madness is tricky – for instance, Carl Jung’s transcriptions of his nervous breakdown, published as The Red Book, are incredibly difficult to penetrate – but each of Farah’s scattered microscenes flow well within themselves. Farah tells the story from the insane first-person perspective of a character named Alain Farah. The approach can be compared to method acting – pretending to be insane, as opposed to a classical actor who would instead create the impression of insanity. The technical challenge is to establish a thread amid the erratic misdirection of an unreliable narrator who is also mentally disturbed. This “method writing,” could also be compared to “method directing”: one actor can pretend to be insane and the piece can hold together, but if the director (i.e., the eyes through which the work is seen) behaves insanely then the entire piece is threatened to descend into high-toned blathering.

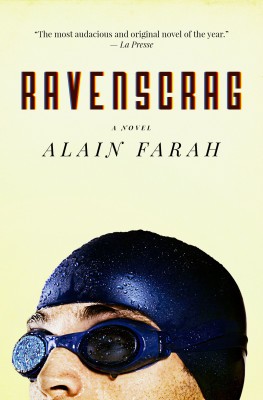

Ravenscrag

Alain Farah

Translated by Lazer Lederhendler

House of Anansi Press

$22.95

paper

224pp

978-1-77089-895-0

Putting setting, events, and characters in a bag, shaking them, and spilling them out on the page risks spoiling the ingredients of the story and borders on being disrespectful of the craft.

Farah is also averse to narrative, which he explains by, again, quoting Scott: “But can’t the emotion felt be just as important as understanding the plot?” Focusing on emotions is a viable approach. Emotion comes from proximity to tension, attachment to characters, or atmosphere. But the rambling madman reduces characters and details to names that are dropped into scenes, without context, thus yielding neither narrative nor emotional value. Farah justifies his approach by saying, “In other versions of this book, the events unfolded without a break. It was seamless: I opened and closed a lot of doors, I moved characters from one scene to the next, in a word: boring…. so I erased the whole thing…. I prefer to tinkle out a few tunes I find enjoyable, even if there are fewer of you on the dance floor.” Elsewhere the authorial character tells us that after his last novel came out, “a bookseller told me ‘Your book is a party, but we’re not on the guest list.’”

Writers like Chuck Palahniuk and Larry Tremblay have proven that linearity and sanity are overrated literary commodities. Readers just need well-constructed characters, stories, and emotions. If writing them is boring, that may be an indication that something is wrong at the source, and it probably won’t get better if the work is put in a blender. A novel needs some element of cohesion – even if it’s only emotional – which Farah never succeeds in establishing. Ravenscrag has wonderful potential: setting, situation, social relevance, all of which are completely squandered in favour of the author’s personal indulgences and justifications thereof. It’s a party with a self-absorbed host and music you can’t dance to: if that sounds like your kind of fun, by all means, buy a ticket. mRb

0 Comments